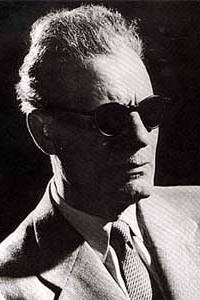

Hussein, Taha (1889-1973)

Article by Abdel Fattah Galal1

Yes, in the darkness and tranquility of the night, I allow myself the indulgence of a beautiful dream. I see an Egypt which has done all I have ever asked, now devoting its whole hearted care and attention to education. I see an Egypt which has achieved all I have ever promised. I see an Egypt from which the mists of ignorance have been lifted, now bathed in the light of knowledge and learning. I see an Egypt in which education embraces all the people, rich and poor, strong and weak, bright and dull, young and old. I see an Egypt steeped in the sweetness of education, an Egypt in which the light of education brightens hovel and palace alike.1

This, then, was the beautiful dream of Taha Hussein, one of Egypt’s greatest thinkers. It was the summation of his experiences in life, drawing together the strands of Egypt’s immemorial past, its modest present and its glittering future. His thinking, which grew out of the very soil of Egypt, was combined with his experiences of Egypt and the Arab world, of Islam and Europe. It was a declaration of war on backwardness and a proposal of alternatives drawn from modern civilization, which he had experienced in Europe, above all in France, his second home. Regardless of the controversy that these views generated, the result was a new vision which remains valid to the present day, and a programme capable of solving the problems faced by education in developing countries and, more particularly, in the Arab world.

This was a dream of democracy and equality, under whose twin banners no one would be excluded from knowledge and education. Together, all would play an active part in the building of a society which was free and democratic, independent and strong. This was the framework of Taha Hussein’s philosophy of education.

In this dream, knowledge was not a luxury but a necessity. It was essential to eradicate illiteracy and provide free primary education for all. Everyone is entitled to education and no one must be neglected, neither the gifted nor the less fortunate. Education is an ongoing process, one that continues throughout life, from youth to old age.

Taha Hussein expressed his dream not in the dry jargon of pedagogical science but in the language of poetry, a language understood by people at every level of educational attainment. Though his dream is shared to this day by all Egyptians – and, indeed, by all humanity – it still remains a dream. It is that dream of education for all which international organizations – with UNESCO in the vanguard – are seeking to translate into reality in every country, so that all children will receive at the very least a primary education, and adult illiteracy will be consigned to history.

The life and thought of Taha Hussein

This dream took shape through many different stages of development: at times Taha Hussein experienced disappointments and faced difficulties, yet he also achieved considerable success, occupying prominent positions in politics and education, and enjoying celebrity as a scholar, not only in Egypt but throughout the Arab world and the West. The phases of disappointment and success which marked the life of Taha Hussein were paralleled by the development of Egyptian society itself.

Taha Hussein was born in 1889 during the period of demoralization which followed the failure of the Arab revolution and the British occupation of Egypt in 1882. He was born and lived his childhood in a small community in the Governorate of Minya in the south of the country. In this environment, poverty and ignorance, disease and destitution were endemic, and there was no provision whatever of preventive medicine or medical care. For this, Taha Hussein would pay dearly, losing his sight at the age of 6.2 His father, a minor civil servant weighed down by the burdens of keeping a large family, could do nothing but enrol him in the village school to learn the Koran. There the child mingled with graduates from al-Azhar and acquired popular culture by listening to storytellers recounting the lives of Antar bin Shadad, Sayf bin Dhi Yazan and other Arab folk heroes. Despite all the difficulties facing him, an intense desire arose in the boy to travel to Cairo and study at al-Azhar.

In 1902, Taha Hussein left for Cairo with his older brother Ahmad and enrolled at al-Azhar, where he continued his studies until 1912.3 This was a time when the Arab national revolt against the British was growing in intensity under the leadership of Mustafa Kamila and would be heightened by the Denshawi incident in 1906. One of the fruits of this period was the creation of the National University, which opened its doors to students in 1908. Taha Hussein took this opportunity and enrolled, since he found the traditional teaching methods employed in al-Azhar at the time too restricted. At the National University he found new ideas, discovering the history and civilization of ancient Egypt and studying Islamic philosophy within an intellectual framework unknown at al-Azhar. He studied under Egyptian and foreign teachers, taking courses in Islamic civilization, the civilization of ancient Egypt, Semitic languages, French, Arabic literature, Islamic philosophy and Oriental history.4 This offered a window onto a new world of thought and culture very different from the one to which he had been accustomed at al-Azhar. He continued his studies until May 1914 when he obtained his doctorate from the National University for a thesis on the life of Abi al-Ala’ al-Ma’arri.5

In view of his academic excellence, the National University sent Taha Hussein on a scholarship to the Sorbonne in France. There, he became a fluent writer of French and studied sociology. He gained a doctorate from the Sorbonne on the philosophy of Ibn Khaldun in 1918 and a postgraduate diploma in the history of civil law in 1919. During his time as a student in France, Taha Hussein studied the new sciences of psychology and sociology, and Émile Durkheim supervised part of his doctoral thesis. He also studied French literature and modern history, learned Greek and Latin and read classical history.6

The pressure of the Egyptian revolt at the time led to the appointment of a new governor and to a slight loosening of the iron grip of British occupation. This gave some glimpse of hope to the National University and to the scholars who had been sent abroad. These included the young Taha Hussein who had absorbed a whole range of cultures – Egyptian, Arab, Islamic, Semitic, Greek, Roman and French. He was adept in taking what was best from his own heritage and combining it with the best in modern European culture. He returned with high hopes of developing education in Egypt.

He arrived back in 1919, the year of the Egyptian revolt against British occupation which resulted in the end of the British Protectorate in 1922. Independence was declared, a constitution was drafted in 1923 and the first parliamentary elections under the new constitution were held in 1924.

Taha Hussein began to teach Greek and Roman history at the National University. He took part in a cultural life vibrant with nationalism and jealously devoted to independence. When the National University was taken over by the state in 1925, Taha Hussein was first appointed professor of Arabic literature and then dean of the Faculty of Arts in 1928.

As an active participant in politics and culture, Taha Hussein could not escape the vicissitudes of this life; for example, he was at one time dismissed from his post in the Faculty of Arts. However, he was to be reappointed later and from then on was known simply as ‘the Dean’. Political and cultural life also had its rewards; in 1942, he was appointed adviser on the arts to the Ministry of Education and, at the same time, was seconded to act as president of the University of Alexandria. He2held these two posts until 1944. The pinnacle of his career was his appointment as Minister of Education from January 1950 to January 1952.

Taha Hussein’s activity was not confined to the academic world and educational administration. For example, during the period from 1939 to 1942, he was an observer on cultural matters for the Ministry of Education. In addition, he both edited and wrote for newspapers and magazines. He was appointed first as a member and then as president of the Arabic Language Academy, and took part in the intellectual, cultural and political controversies of the day. He attended numerous academic conferences at home and abroad.7 From 1952 until his death in 1973, he lived the life of an ordinary university professor of Arabic literature in the Faculty of Arts of the University of Cairo (formerly the Egyptian University).

The bulk of Taha Hussein’s considerable body of works are concerned with Arabic literature. On education, he wrote just one book, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa fi Misr [The Future of Education in Egypt], and translated Gustave Le Bon’s Psychologie de l’éducation in 1921. Even so, he continued to write articles and give lectures on the subject from 1938 almost up to the time of his death.

The experience of administration, public service, politics and culture all helped to form and strengthen Taha Hussein’s thought and add depth to his vision. He was not content to confine himself to the world of theory but combined his intellectual pursuits with the needs and aspirations of a nation striving for complete independence and freedom and, as Egypt has done throughout its long history, to make an effective contribution to human civilization.

Against this background of nationalism Taha Hussein, drawing on a wealth of sources, wrote The Future of Education in Egypt.8 Although he would continue to publish articles on education and to give public lectures after the publication of this book, analysis of his later work reveals no new, comprehensive vision or intellectual framework, but rather commentary on various aspects, defence of one position or another, or attacks on opposing viewpoints.

The general framework of education

When a society has come through a major crisis, such as military subjection to a foreign power, domination by a hostile culture or abrasive contact with other cultures, it is faced with the need to seek and redefine its identity. It has to decide what constitutes its national character. It has to examine its culture and distinguish between the enduring and the ephemeral, between old and new values, between tradition and modernity.

Developing countries in general and, more particularly, those that were subject to colonialism in one form or another, were almost all obliged to search for their identity, questioning the basis and the manifestations of their culture. Egypt itself was no stranger to this question of identity. With the French occupation in 1798, Egypt discovered that its culture had become stagnant and that it had been overtaken by other countries in areas which enabled them to impose their sovereignty. Thus, it began to question its attitude towards its own culture. The result was an opening up to Europe and modern civilization which gave rise to a debate over tradition versus modernity.

Opinion was divided between those who clung to tradition and those who asserted that Egypt should follow Europe. It was to be expected that an intellectual like Taha Hussein would make his own contribution to this debate, which formed the general framework for education and defined its aims.

The starting point for Taha Hussein’s definition of Egyptian identity was his study of classical, medieval and modern history: ‘The new Egypt will be inventive or creative only in so far as it is founded on the eternal Egypt of its past… For this reason, I can think of the future of education in Egypt only in the light of its remote antiquity.’9 Thus, Egypt’s ancient past was taken to be one pillar of the country’s cultural future and one of the main features of its national character. A second pillar of Egyptian culture taken from history was its civilization:

It is a waste of time and effort to try to separate the relations between Egypt and the ancient Aegean civilization, the relations between Egypt and the first ages of Greek civilization and the relations between Egypt and Greek civilization which blossomed in the sixth century B.C. and flourished up to the days of Alexander.10

Taha Hussein stressed the importance of this element:

The exchange of ideas between Egypt and Greece in ancient times was something which the Greeks honoured in both poetry and prose. Egypt is spoken of in the highest terms in Greek epics, in dramatic poetry, in the works of Herodotus and the writers and philosophers who came after him.11

The third pillar of Egyptian culture was Islam and the Arabic language: ‘Islam, which came and spread throughout the world, was warmly received in Egypt where it was swiftly embraced as the national religion and Arabic, the language of Islam, was adopted as the national language.’12

The selection of these pillars of Egyptian culture clearly demonstrated the influence of Taha Hussein’s varied background and a mind formed, as we have seen, by al-Azhar, the National University and the Sorbonne. The same influence may be seen in his intellectual and administrative efforts to develop Egyptian education. He concluded from these pillars of culture that the Egyptian and the European mind are alike: ‘From the earliest times, if the Egyptian mind was influenced by anything, it was by the Mediterranean; if benefits were exchanged, they were exchanged with the peoples of the Mediterranean.’13 This influence acted on the Egyptian mind no less than on the European mind; it was simply circumstances which affected one or the other of them in disparate and contrary ways. Just as the European mind played its role in human civilization, so too did the Egyptian mind in ancient times and in the Middle Ages. Egypt had safeguarded the heritage of human thought in two ways: first by giving a home to Greek philosophy and civilization for more than ten centuries, and again by fostering and protecting Islamic civilization up to modern times. He concluded by saying:

Thus, everything goes to show that there is no such thing as a European mind distinct from the oriental mind of Egypt and the neighbouring countries of the Near East. On the contrary, there is a single mind which varies because of disparate and contrary circumstances, the effects of which are disparate and contrary influences. In essence, it is one and the same mind, without distinction or difference.14

Taha Hussein demonstrated that from the beginning of the nineteenth century, Egypt, like Europe, adopted the amenities of modern life whole heartedly and without any sense of unease. All aspects of Egyptian life, whether material or moral, became Europeanized. He cited many examples of this in Egypt, from the building of railways and the laying of telegraph and telephone lines to the introduction of cabinet government and the parliamentary system. And it was the same with the modern education system:

It is beyond doubt or dispute that our education system – no matter what we do with the structures or with the curriculum and syllabus – has been purely European since the last century. Our children in primary, secondary and tertiary education are being formed to an entirely European pattern.15

Taha Hussein came very close to rejecting Islamic and Arab nationalism, proclaiming an Egyptian nationalism and patriotism within the framework of Mediterranean civilization and from a European perspective:

However, there is a new form of nationalism and patriotism which has arisen in this modern age and which underpins the life and relations of nations. It has been introduced into Egypt together with the products of modern civilization.16 He argued that politics is different from religion and that the system of government and the structure of the state are founded on utilitarian concerns.

In defending the necessity for strong and open ties with Europe, Taha Hussein saw no threat to the Egyptian character: ‘There is no difference between us and the Europeans, whether in essence, character or temperament’.17 Thus, Egypt had nothing to fear from being assimilated completely into Europe.

In this context, Taha Hussein defined the traits of the Egyptian character as being shaped by geography, religion, the Arabic language, the artistic and literary heritage, and a long and glorious history.18

Among these traits, he singled out the qualities that distinguish Egyptian culture from that of other countries. He saw them embodied in national unity and deeply and intimately linked with the spirit and existence of both ancient and modern Egypt.19 Finally, they may be seen in the adoption of Arabic as the language of Egypt – an Arabic which differs from that spoken anywhere else: ‘That the Arabic language is common to Egypt and the other Arab countries is certainly true. Yet, the Egyptian mode of expression is as individual as the Egyptian mode of thinking.’20

Thus, Taha Hussein believed that the characteristics of Egypt were unique, though they might resemble those of certain other Arab and non-Arab societies. This reaffirmed his position on Egyptian nationalism and the individuality of its culture: on the one hand, he rejected the call to Islamic nationalism which he had backed before he had dictated The Future of Education in Egypt; on the other, he implicitly rejected pan-Arab nationalism, though this call would not become powerful until after the Revolution of July 1952. At the same time, however, he did not regard opening up to and borrowing from Europe as a danger to Egyptian culture, the primordial elements of which are to be found in Egypt’s ancient art, the Arabic-Islamic heritage and modern European life.

There is in this country an Egyptian humanist culture. It partakes at once of the character of Egypt, ancient, peaceful and eternally enduring, and, at the same time, of a humanity which is capable of winning hearts and minds, of bringing people out of darkness into light and of giving them a pleasure and enjoyment which they may or may not be able to find in their own culture. This culture has educated and given pleasure to many non-Egyptian Arabs and the little of it which has been translated into other languages has surprised and delighted the European reader.21

Therefore, the distinctive traits of this culture arise from the ancient history of Egypt, from Islam and the Arab heritage, and from the civilization of modern Europe. To Taha Hussein’s mind, therefore, it was essential that the goals of education and the content of the curriculum should preserve this Egyptian identity and its characteristic traits, within the framework which he had conceived for the future of education in Egypt and the formation of future generations. In this regard, we do not wish to dwell on the politics of those who supported Taha Hussein in his conception of Egyptian cultural identity and characteristics, or those who opposed him fiercely or considered that he had gone to extremes in his idea of linking Egypt with Europe.22 What is put forward here is the idea that the identity of any society must be defined by its own people. They must be aware of the traits of their own culture and, while accepting the amenities of the modern age, they must take care to preserve the eternal aspects of their national character. Equally, they must be aware of the changing world around them and be ready to adopt attitudes with regard to the changes. Finally, every society must be aware of the repercussions of all this on education and curricula at the various levels.

The goals of education

Everywhere, the objectives of education spring from higher goals laid down by society. When Taha Hussein set out his view of an Egypt of the future, it was in keeping with his own conception of Egyptian identity and of the Egyptian mind as being similar to the European mind. This picture stemmed from the influences of French culture, the principles of the French Revolution and from the Islamic heritage, as well as from the suffering he had endured in a childhood of relative poverty in the Egyptian countryside. In those days rural Egypt lacked both education and health care. He believed that the goal of education should be to achieve equality between all Egyptians:

Aristotle was guilty of a grievous error when he asserted that some are born to command and others to obey. Never! We are all born to be equal in rights and duties and to receive the benefits and burdens which fall to our lot in this life. When oppressors rise above the people, it is we ourselves who must cast them down; and when tyrants emerge, it is we ourselves who must remove them.23

Although Taha Hussein focuses on equality as an educational goal per se, it is one derived from democracy:

If we seek to summarize the fundamentals which democracy should provide the people, we will find nothing more succinct, nothing more comprehensive, nothing truer than the words proclaimed by French democracy two years ago, namely that the democratic system must provide all the people with life, freedom and peace. I do not believe that democracy can provide the people with these fundamentals if it fails to provide a system of universal primary education which is accepted by all the people, whether voluntarily or compulsorily.24

Taha Hussein did not confine himself to primary education but demanded that public provision should be expanded to cover secondary and higher education. This, he believed, would ensure the achievement of democracy in Egypt. He affirmed that any democracy which went hand-in-hand with ignorance would be based on lies and deception; any parliamentary system which went hand-in-hand with ignorance could be no more than pretence and delusion. If the people are the source of power, they must be given the opportunity of education, for power should never spring from ignorance. It is only natural that education, in a democratic system, should seek to achieve freedom for everyone. As far as Taha Hussein was concerned, freedom and ignorance were mutually incompatible. Real freedom arose when education imbued the individual with a public spirit, and made him aware of his rights and duties, as well as the rights and duties of his fellow citizens.25

A democratic system which gives freedom to its citizens will ensure an education which provides and promotes peace among them, instead of leading them down the paths of tyranny and aggression:

A man who has no freedom is incapable by his very nature of creating and defending peace. Indeed, he is incapable by nature of even conceiving of such a peace. He is capable only of living under oppression and, given the opportunity, will more often than not become an oppressor himself. Democracy will not be able to provide people with life or freedom or peace unless it gives them an education which enables them to enjoy life, freedom and peace.26

According to Taha Hussein, education should aim at creating social justice; this is the counterpart of equality and both of them are rights which everyone should enjoy. He rejected out of hand any suggestion that charity has a role to play in matters of social justice, such as the right to education. He believed that the people have an absolute and sacred right to see equality and justice prevail among them, without distinction:

Though the circumstances of history may have divided them into rich and poor, and though nature may have divided them again in terms of capacity and ability, yet, there is one thing that they share and is the same for all of them; in the saying of the Prophet, they are human beings; from dust they have been created and to dust they shall return. Therefore, leaders and rulers, lords and masters must rid themselves of any notion that they are superior to the people; they must rid themselves of any sense that they are doing a work of charity, for such charity is but one facet of superiority. These notions must be replaced by a belief in equality and justice among the people.27

These feelings must become part of Egypt’s way of seeing and judging the world, and a basic component of its sense of nationhood. All Egyptians will then share in the belief that they have a right to a decent and dignified life, and that education and culture in all their various forms are the means by which to attain this decent and dignified life. All Egyptians will believe that education is as important and valuable as life itself.

Within the framework of this democratic society, it will be possible to preserve the independence for which citizens have willingly shed their blood and to build a society which is strong militarily, economically, socially and culturally. Yet nothing can be achieved without knowledge and learning. Freedom and independence are but the means to an end, namely the building of a civilization ‘which is founded on education and culture, owing its strength to education and culture, and deriving its prosperity from education and culture’.28 This, in turn, can only come about by raising a proud, strong army, by establishing a progressive national economy and by achieving independence in science, art and literature. ‘There is one way to achieve all this and one way only, namely to found education on a solid basis’.29

Objectives at various stages of education

Displaying either originality in terms of organization or familiarity with developments in Europe, Taha Hussein took the main objectives of education and subdivided them into subsidiary objectives for each stage.

Primary education (or ‘elementary’ as it was called then) should have four objectives: (a) to achieve national unity; (b) to unify the national heritage; (c) to prepare the student for work; and (d) to train young people so that they are capable of developing and becoming useful to themselves and to the nation. He believed that the democratic state had a duty to provide primary education for a number of aims:

Firstly, primary education is the easiest means to enable the individual to earn a living. Secondly, primary education is the easiest means to enable the state itself to achieve national unity and to make the nation aware of its right to a free and independent existence which it has a duty to defend. Thirdly, primary education is the only means available to the state to enable the nation to survive and maintain its existence. Through primary education, the state can guarantee the basic unified national heritage which has to be transmitted from one generation to the next and which must be taught to and learned by all individuals in every generation.30

To this list, he added the student’s ability to develop and the capacity to be of benefit both to himself and to the nation.31 But Taha Hussein did not wish to see the notion of development confined to the development of the body or the mind; he extended it to include morality and ethics: ‘They are developed in mind and body; they are pure in heart; they are sound in morals.’32 Moreover, development leads to the formation of ‘responsible citizens who are of benefit to the society in which they live, who are worthy of the nation’s trust… who are trained to defend the nation and to establish security and justice, who are enabled to prosper and to aspire to a better life’.33

Thus, Taha Hussein was among the first to appreciate the role of education in the full development of the child, both as an individual and as a member of society. At a time when mental development was held to be of utmost importance, he stressed every aspect of development: physical, mental, emotional, social and economic. With regard to the mental aspects, furthermore, he was not content to stop at mere ‘knowledge’ but insisted that children should also have ‘good understanding, judgement and appreciation’. He summed this up as the ability to understand life and development, together with all the resulting implications for themselves, their families, their country and people as a whole.34

His concern for national unity arose because of the diversity of elementary schools, which included government, private, religious and foreign institutions. Realizing the threat this posed to national unity and social cohesion, he called for all types of primary education to be standardized – a statement which is now taken for granted in the world of education. He linked this aim with the unity of the national heritage and its transmission from one generation to the next. This was tantamount to saying that in order to attain cultural development, individuals must be allowed to prosper and aspire to a better life. He thus stressed the dual function of education in relation to culture, namely to preserve culture by transmitting it to the next generation and to develop its component parts by addition and innovation.

Let us now turn to the aim of preparing the individual for work or, as Taha Hussein would say, ‘enabling him to live’. This is still a subject of controversy among educationists. The majority view is that primary education could – but does not – prepare the child for work. However, when education is extended to the next stage (preparatory, intermediate or lower secondary), the child is often better prepared.

In general, the aims which Taha Hussein put forward for primary education are still valid for basic or compulsory education in many countries. He recognized this when he spoke about children whose education would stop at the end of the elementary stage and who would then enter the world of work. He believed that the state owed them something: ‘they should not be ignorant of what they need to know, they should not forget what they have learned and they should not be restricted to what7primary school has taught them’.35 It is as if he were calling for compulsory education to be extended to the following stage, although what he proposed was adult or extra-curricular education in which the state would organize ‘simple evening classes which such people could attend after they had finished work. This would be neither purely compulsory, like elementary education, nor would it be purely voluntary and left entirely to their own volition’.36

As far as secondary education is concerned, Taha Hussein proposed three objectives: to prepare young people for a decent and productive life;37 to prepare pupils for higher and university education;38 and, as an extension to the objective proposed for elementary education, to achieve national unity based on independence in relation to the outside world and freedom at home.39

The goals of both primary and secondary general education were to achieve national unity, to educate the individual in order to adapt him/her to the material and spiritual environment, and to promote a sense of belonging to one’s community and nation. Taha Hussein believed that primary education represented an introduction to later stages. For this reason, he must be prepared simply and gradually with the utmost care and attention.40

Primary education, therefore, is a preparation for secondary education which, in turn, is a preparation for higher and university education. In this way, the social and cultural goals of general education are perpetuated.

With regard to higher education, Taha Hussein defined the objectives as preparing students for work in high public office and training their minds so that they become cultivated individuals. When laying down the aims of third-level education, he rejected the view that ‘higher education is something sacred… the quest for knowledge for its own sake and the preparation of young people for this pure and sacred quest unhindered by the necessities of practical life’.41 He believed that higher education meant a superior degree of culture and that it was a necessity for anyone wishing to earn a living by entering a particular post or employment.42 Higher education, therefore, provided ‘a route to the practical world and not to some state of Platonic happiness’.43

Nevertheless, his proposed aims for higher education did not neglect pure academic research. He believed that:

it is right and appropriate that higher education should combine academic research into both the pure and the applied sciences, for, without the former, the latter could not exist, produce, survive or provide people with the amenities and luxuries of civilization.44

For Taha Hussein, ‘the university must be a seat of learning, not only by its own standards but by comparison with other environments as well’.45 Equally,

it must be a seat of the highest civilization and excellence, the influence of which is seen not so much in academic or practical results as in a life of purity and rectitude in human relations, in love and mutual respect, in putting obligations before rights, in asking what we owe others rather than what they owe us; it is rising above the self and transcending the petty and the worldly to a refined aesthetic sense which turns towards beauty when it is perceived and which turns away from ugliness when it is perceived.46

Taha Hussein returned to the topic of the general objectives of education, insisting that:

We must not look upon the universities and educational institutions in general as schools which simply impart knowledge and form minds. Knowledge by itself is not everything. It is high time that we believed and became convinced that educational institutions are not simply schools but are, above all, environments for culture and civilization in the widest sense.47

By this definition, all educational institutions – primary and secondary schools, institutes of higher education, university faculties – serve to form individuals capable of preserving independence and ensuring equality, freedom and social justice for all members of the nation. These individuals will construct a modern civilization in a democratic society founded on culture and learning.48

Education, national defence and the judiciary

If education is the means by which to establish a democratic society and civilization, it must be given the highest priority by decision-makers. Taha Hussein, with his customary acuity, was one of the first thinkers of his age to insist that education was a basic need rather than a luxury and that government expenditure on education was no less essential than spending on national defence. Education and national security are one and the same:

When we demand that education be fostered and made universally available, we are not asking that the people should be pampered and given something they could abstain from or do without. No, what we are asking for is that they should be given the most basic of their rights, the very least that they deserve. The people’s need for a proper education is no less a necessity than the nation’s need for strong defence. The people are threatened not only from without by the incursions of predatory foreign powers but also from within by an ignorance which undermines their moral and material environment and places them in bondage to the superior knowledge of the foreigner. The fact that Egypt has a mighty army to protect her territory and boundaries will not ensure true independence if the people behind the lines to the rear are ignorant and unlettered, incapable of exploiting their land and all its resources, incapable of managing their own amenities, incapable of winning the respect of the foreigner by their contributions to human progress in science and philosophy and in literature and art.49

If Taha Hussein felt – as indeed he did – that education was so important, so valuable and of such high priority, then knowledge and education were to be held sacred and the teacher was to be honoured and respected in every way, academically, socially and materially. For this reason, Taha Hussein held that education should be put on a par with the judiciary, and the teacher should be placed on the same footing as a judge. He felt that those whose task it is to spread knowledge among the people must be honoured in the same way as those whose task it is to ensure justice.50

The question of educational expenditure and the priority which it deserves continues to occupy an important place in educational thinking throughout the world. Ever since the recommendation of the International Governmental Conference held in 1966 by UNESCO and the International Labour Organisation, the question of improving teachers’ status has remained a matter of concern for those seeking to achieve the objectives to which Taha Hussein aspired.

The need for state supervision

Taha Hussein raised the issue of state supervision thirty years before Egypt’s 1971 constitution stipulated that the state must oversee education of every kind and at every level. He called on the state to supervise not only foreign and private institutions but even religious education. At the same time, he called for the elimination of differences in curricula and programmes, particularly where such divergences were prejudicial to national unity, social harmony and the sense of Egyptian identity. His opinion was that only the state must designate and implement the curricula and programmes of education, and it must supervise them closely to ensure that education does not stray from its intended path and pursue other objectives.51

In a pioneering step, Taha Hussein called for the teaching of religion, the Arabic language, and Egyptian history and geography in the foreign schools established on Egyptian soil and for the state to ensure that these subjects were actually taught by means of monitoring, inspection and testing. At a time when the Ministry of the Interior had responsibility for overseeing education within local administrative boundaries, he called for the Ministry of Education to be the sole state institution responsible for the supervision of education in terms of curricula, inspection and examinations.

In another pioneering initiative, he called for state supervision of private schools to ensure that the educational objectives achieved were those set by the state. He also called for variety and diversity among schools, provided that this did not affect the development of the national character in every pupil. He even went so far as to demand that general education in al-Azhar, within the framework of variety and diversity, should be placed under the Ministry of Education in order to ensure that it remained consistent with the subjects taught in state schools. He was careful not to confuse state supervision of private education with measures which might hinder participation by individuals, 9organizations and the private sector in establishing schools and financing education. On the contrary, he was eager to see this partnership continue, viewing it as necessary if education were to be provided to all citizens. When Taha Hussein became Minister of Education, he was able to put some of these ideas into practice. For example, Law No. 108 of 1950 removed local municipal schools from the supervision of the Ministry of the Interior and placed them under the control of the Ministry of Education.52

Free education

The question of free education occupied an important place in Taha Hussein’s thinking and practice. It was only logical that he should insist on free education, since he himself had experienced material hardship in his childhood and had been prevented from enrolling in a state school through the fees imposed by the British administration. These constituted a heavy burden for the great majority of Egyptians and denied children their right to enter primary education. The only alternative open to Taha Hussein was a pale shadow of education far beneath his ambitions, namely the blind alley of the kuttab or Koranic school and an elementary education which led nowhere, save for the gifted few who were able to join al-Azhar. While this might be easy enough for those living in Cairo, it entailed great sacrifices for rural families. His experiences impelled him to uphold the principle of free education, a system which he had known in France and the benefits of which he wanted his fellow countrymen to enjoy.

Taha Hussein’s position with regard to free education stemmed from two sources: the constitution of 1923 which made primary education compulsory; and the principles of democracy:

There is no need to dwell overly long on the fact that compulsory primary education is a fundamental pillar not only of true democratic life but of social life whatever the system of government… Egypt has adopted this position in full since the promulgation of the constitution, which imposed compulsory education and required the state to uphold it and compelled parents to send their children to school.53

Taha Hussein conceded that since secondary education was not compulsory, it would not be given to everyone free.54 However, he insisted that it should be provided free to the poor:

Firstly, they have a right to secondary and higher education; secondly, this is in the national interest; thirdly, this serves to achieve democracy. To deny education to the poor because they are poor and to prevent them from advancing, from bettering themselves and from aspiring to the best is but to strengthen the class system, to lend credence to the power of money, to kneel before its power and to perish with it. There is not one iota of democracy in any of this.55

The right to a free education should be allowed to anyone who can show that he is truly ready to benefit from it.56

At first, Taha Hussein was ambivalent about the right of everyone to free secondary education. At times, he said that it should be restricted to poor pupils who had demonstrated their aptitude; there would, of course, also be those children of the well-off whose parents would pay for them. At other times, he was inclined to reduce school fees so that the poor could enjoy this opportunity. He gave qualified approval to the experience of France, which had adopted the principle of free secondary education: ‘The path which French democracy has followed is righteous and does justice to the needs of the poor, but it is a course which is not without extravagance.’57

As soon as Taha Hussein found that free primary education had become a reality, he promptly called for free secondary education.58 He then went even further, saying that it was as natural to provide people with education as to allow them the light of the sun, the air they breathe and the water of the Nile. This image made such an impression that, when Taha Hussein was appointed Minister of Education in 1950, he was popularly known as ‘the Minister of Air and Water’.59 The principle that general secondary and technical education should be free was reinforced when Taha Hussein promulgated laws on them in 1950 and 1951. The only exception was for pupils who had repeated two years at secondary level or who were over 21.60 Taha Hussein’s success in giving Egypt free primary and secondary education was completed by the Revolution of 23 July 1952 and by the 1971 10constitution which enshrined the principle of free education at every level of general, higher and university education and in every state school, institute and faculty.

The expansion of education

True to the logic of his thought and beliefs, it was only natural that he should call for an expansion of general and higher education.

Taha Hussein discussed the relationship between the expansion of education and graduate unemployment, a question which remains a matter of controversy to this day in developing countries, including Egypt. Some argue that the opportunity for higher and university education should be restricted because expansion in this area leads to graduate unemployment and has negative social and economic consequences. He strongly opposed anyone advocating that the expansion of education should be restricted in a democratic society. He argued that to do so would be to espouse ignorance as a basis for national policy; it would mean creating a class system in which an aristocracy would enjoy education and monopolize power and government, while holding the ignorant majority in subjection. In this way, Taha Hussein defended the expansion of education both on the grounds of democracy and on the grounds of improving the level of education. He pointed out that primary education alone (i.e. low-level education) was insufficient for a citizenry which is not easily duped. As he said: ‘Education and education alone – provided that it is sound and well guided in its methods – will ensure that Egyptians are treated with justice and equality at home and abroad.’61

The truth is that an education which is sound and well guided in its methods will create opportunities for work, overcome the problem of unemployment and, most important of all, create human beings who cannot in any circumstances be duped. Such citizens know how to get at the sources of truth and reality, are concerned for the security and stability of their country, for the peace and safety of all humanity, and for progress and prosperity; they cannot be led astray by factions, extremism and bigotry. Even if, for the sake of argument, it was conceded that graduate unemployment was inevitable, the answer to the problem does not lie in ignorance because ‘ignorance is an evil per se and one evil can never serve to cure another’.62 Instead, Taha Hussein drew on the experience of European countries in dealing with the problem of graduate unemployment, and proposed a number of practical solutions which remain valid to the present day:

Education itself is being diversified in such a way that not all students are poured into the same mould or forged to the same pattern. On the contrary, an element of diversity is being introduced and encouragement afforded to competition, personal endeavour and originality, so that education gives students a good preparation and enables them to face life without any feelings of inadequacy, worry or despair.63

Taha Hussein raised the whole issue of how obtaining educational qualifications relates to finding employment, a matter which remains contentious, particularly in countries like Egypt. In this context, Taha Hussein said: ‘This means that university degrees and diplomas are not enough to qualify those who hold them for posts of any kind. Instead, positions should always be awarded on the basis of competition.’64

Taha Hussein believed that there was an enormous difference between passing academic examinations and seeking a livelihood, and he rejected the idea that the two should be linked:

Examinations are the means to obtain a university degree and nothing more. It is virtually impossible for the student to complete them successfully until he has been prepared for a far more serious competition which will influence his life and it is this which will lead him to find a post.65

Nowadays, the trend is to award posts not on the basis of the degree which a candidate has obtained but rather in accordance with a specific profile of abilities, skills and experience needed for that type of work.

Financing education

Any expansion of education is faced with obstacles in terms of financial, material and human resources, i.e. the necessary financing must be available. Here again, some might say that the opportunity for education should be restricted and, once more, this is a view which Taha Hussein rejected out of hand:

The state must find the necessary funds, just as it finds the funds needed for national defence. This is not impossible or even difficult in our modern world. The state can shut off many avenues of waste and apply the funds to education and national defence. The state can make savings in many areas and use the proceeds for both education and national defence.66

Taha Hussein called on the state to impose taxes to pay for education and to levy them on those capable of paying. The state is entitled to see a return on its educational investment from those with the ability to pay.67

Taha Hussein stated the principle that expenditure on education should be properly directed. For example, he pointed to the extravagant spending on school buildings and called for a more modest approach to reduce costs. The point was to focus attention on to the need for well-directed spending and the possibility of constructing low-cost schools from raw materials readily available in the local environment. As Minister of Education, he himself sought to reduce the cost of free secondary education by excluding pupils who failed two years running. Taha Hussein also sought to encourage the private sector to play a role in expanding education: ‘I, more than anyone, am eager to encourage private initiatives by individuals and associations, not just for the sake of education but for the public good as a whole.’68

Thus, Taha Hussein proposed various means of financing education, whether by the state, by individuals and associations in the private sector, or by those who were well-off and able to contribute. He also wanted to impose an education tax and see spending properly managed in order to increase budget allocations for education. At the same time, he suggested ways of structuring educational expenditures – for example, through more appropriate construction or by rationalizing the provision of free education – and, more importantly, he proposed alternative means of finance. Finally, he made the state face up to its responsibilities by giving priority to educational expenditure.

Teacher training and employment conditions

Any democratic society striving to develop its culture and consolidate its civilization on the basis of science and education must pay due attention to the position of the teacher. It is not enough that the curricula and programmes be excellent; they should also be implemented properly and productively. This can only be done by good teachers who understand the curricula and programmes and implement them in the best possible way.69

Taha Hussein devoted a whole section of The Future of Education in Egypt to a defence of the rights of the teacher. He took as his point of departure the example of the educator represented in the Arab-Islamic tradition: a tutor whose task it was to prepare and develop the sons of the ruler to assume the tasks of government, administration and leadership, instilling in them the uprightness befitting an exemplar who must direct and manage the affairs of the people:

If we ask the teacher to serve as an educator in the old sense of the word, his task is not merely to fill the pupil’s head with knowledge but more importantly, on the one hand, to train and discipline his mind, to make him upright and to prepare him for practical life and, on the other, to raise his intellectual level. The first duty that we owe to this tutor is to trust and have confidence in him and to make him aware of our trust and confidence.70

When we give the teacher our confidence in this way, it follows that he will look upon the child as a pledge entrusted to him and placed under his protection, to be developed and looked after with the utmost care. Thus, he must look upon himself as being in loco parentis, as being the guardian of the young people he is called on to train; he must not look upon the child as raw material with which he has to work in order to make his living. If the teacher treats the child as a mere object, he himself becomes no more than an instrument, losing confidence in himself, losing the love that he should feel for his profession and losing his belief in the respect due to this profession. ‘Yes, the teacher becomes a tool, the school a factory and the pupils raw material. And education and teaching are devoid of the life, love and activity which should be their essential components.’71 This viewpoint is an early 12criticism of the ideas put forward by economists from Adam Smith to Karl Marx that education represents ‘investment in human resources’.

During the 1950s arose the new science of educational economics, which borrowed a variety of concepts from industrial economics and applied them to education. While it is true that mankind has gained a great deal from all this, something of great value has been almost entirely lost, namely, the idea of education as a ‘vocation’. The materialist notions of economics are far removed from moral concepts and cannot subject them to its criteria. Though educational economics may be required for finance, for seeing that money is well spent and for laying down the criteria of internal and external efficiency and other important matters, it is a science which is redundant when discussing the moral aspect of the teaching vocation. Taha Hussein was ahead of his time when he rejected the idea that education could be assimilated in the production process and said that, if education were no more than that; then it would lose the vital ingredients of life and love, activity and ambition.

Taha Hussein was a forceful defender of the respect due to teachers and the teaching profession. He argued that teachers’ salaries should be increased in order to enable them to meet all their material needs without having to rely on other sources. Only when they are content and confident in themselves can they instil contentment and confidence in their pupils:

A teacher who is reduced to begging in order to feed and educate his own children cannot inspire respect in his pupils. Honour and respect can never be won through servility; a man who is scorned by himself and others cannot win the esteem of his pupils.72

In defending the honour of teachers and their right to higher salaries, Taha Hussein did not confine himself to words. When he became Minister of Education, he established the first ever teachers’ union in 1951, the first article of which stipulated that the objects of the union included efforts to raise the standards of the profession and to promote the moral and material interests of its members.73

In addition to his positive attitude with regard to the rights of teachers, Taha Hussein clearly insisted that proper attention must be paid to primary-school teachers. Their salary should reflect the importance of their work and they should be honoured and respected by people at large:

If the state feels concern about primary education, it must pay proper heed to the primary-school teacher. No matter what the level or grade, sound education is impossible without competent teachers but the competence of the primary teacher is of greater consequence than that of any other group of teachers.74

If this were true, then Taha Hussein felt that it was essential for the state to ‘concern itself with the schools and institutes which provide graduates for elementary education’.75 He called for attention to be paid to training, to budget allocations and to the provision of social, economic and health care for student teachers. He was also ahead of his time when he insisted that the training of primary-school teachers should be at the same level as that of teachers in higher education, and that successful completion of secondary-school studies should be a prerequisite for enrolment in the colleges and institutes for the training of primary-school teachers:

Some people thought that I had gone too far when I made secondary-school matriculation a precondition for entry into teacher training college. However, this is what modern democracy requires and it is required no less by us if we are serious and determined in our wish to form future generations.76

In other words, Taha Hussein was arguing that elementary education should not be made the province of mediocrity. Moreover, he was propounding this view at a time when it was widely believed that anyone capable of learning a textbook by heart was capable of working as a primary-school teacher, and when people with no academic qualifications could be issued with a so-called ‘licence to teach’. His conclusion was that primary teachers and their supervisors should be drawn from the cream of the teaching profession.77

If we applied Taha Hussein’s views to the present-day situation, a Master’s degree, if not a doctorate, would be required of primary-school teachers and their supervisors. These conceptions did not represent a great leap forward but drew on the training concepts which prevailed in Europe at that13time and were in keeping with current systems for training elementary teachers. The important thing is the general concept, which reflected all that was best in teacher training in the advanced countries.

With regard to secondary education, Taha Hussein believed that teachers should attend a university to obtain all the academic subjects needed for their first degree, and then carry on to gain a diploma in education from a specialized university institute. It was the dream of Taha Hussein that teachers would have to pass their Master’s degree before being allowed to teach in secondary education.78 The advantage of this system of training is the depth which it gives to the teacher in his special field of study.79

Taha Hussein rejected the notion of a system of faculties of education in which teachers would combine academic study in a special field with pedagogical studies, a system which, according to him, ‘prevented the student from achieving mastery of either’.80

Another of Taha Hussein’s innovatory ideas was his proposal to adopt the probationary system followed in medical faculties:They are appointed to do practical work in schools on a modest salary for the first year while they continue to study and attend some lectures at the institute. If they complete the year and obtain certification from the institute, they are confirmed in their post and put on full pay.81

Taha Hussein was well aware of the importance of in-service training. He insisted that teachers should remain in close contact with the university and go on to obtain higher degrees: ‘This would enable teachers to master their subjects and, in exceptional cases, might even permit successful specialists to become academics and teach in the university itself.’82 He also called for the establishment of a special university degree to follow the teaching diploma. For this purpose, teachers should be allowed to engage in full-time study or, at the very least, their teaching load should be reduced.83

Issues in education

Taha Hussein’s interests extended beyond mere theory to a number of practical considerations. Some of these were specific issues confined to their own particular time and place, such as the diversity of primary and junior schools and the differences between schools run by the state, religious establishments controlled by al-Azhar, and private-sector institutions teaching in English, French, Italian, Greek, German, etc. He called for all of them to be brought under state supervision and for them to teach Arabic, religious studies and the history and geography of Egypt.84 He was to achieve this objective and it is now universally accepted that the state has the right to control education within its territorial boundaries.

Other issues, however, transcended the confines of time and place and were of concern to the whole world of education. For example, he held that elementary education had to cover reading, writing, arithmetic, national history and geography, civics and religious studies. Referring to the ways in which religious education was viewed in different countries, he argued that it could not be omitted from elementary education in Egypt.85

Another important issue was the eradication of illiteracy, which was prevalent at the time. Taha Hussein believed that young people in the villages had to be taught more than just reading, writing and arithmetic. To confine education in this way was to endanger social stability, curtail talents and run the risk of a return to illiteracy.86 Here again, he was in advance of his time, calling then, as we do now, for quality and functionality in programmes to eradicate illiteracy and for continuing education. Furthermore, cultural resources should be made available to those who emerge successfully from literacy programmes.

A further problem was that elementary education was too short and it was necessary to extend the compulsory period. Taha Hussein devoted a chapter of his book to the reality of this problem. He proposed a number of alternatives, both formal and informal, one of the most important features of which was his stress on physical education.87

Other issues dealt with by Taha Hussein included: a review of the different levels of the general education system, which he proposed should be divided into three levels – primary, preparatory and secondary;88 the problem of overcrowding and large class sizes, which reduced the quality of the educational process;89 reform and decentralization of the administration of education;90 improvement of the schools inspectorate;91 and reform of the examination system.92

It is fair to say that Taha Hussein was a true pioneer in educational matters and that many developing countries, including Egypt, have yet to adopt his proposals. For example, he advocated that, from elementary education upwards, pupils should be given guidance and counselling, that their aptitudes should be defined and their performance monitored, and that their parents should be advised on the most suitable type of education.93 He also favoured what would nowadays be called ‘individualized’ teaching, particularly in languages and the experimental sciences. He felt that these are ‘subjects which are taught not to groups but to individuals, that is, the teacher is obliged to direct his attention to the individual pupil to ensure that he is benefitting from language study’. And Taha Hussein would soon come to see that all secondary-school subjects should be directed at the individual rather than the group, at the pupil rather than the class.94 He also believed that greater attention should be paid to more extensive reading rather than simply to the school textbooks.95 Equally, he felt that the Ministry of Education should confine itself to drawing up curricula and approving textbooks used in schools. It should not itself engage in a commercial activity for which it was unqualified by writing and commissioning such works or purchasing their copyright. There were educational advantages in a system of competition for the writing of textbooks and in authorizing a number of books for each subject instead of just one.96

One of the educational issues which remains controversial and a subject for debate even in the developed countries is the teaching of foreign languages. Here, Taha Hussein insisted that it was first of all essential to pay attention to the national language – in Egypt, Arabic – during elementary education and that it should not face competition from any other language during this period. In answer to the question as to when foreign-language teaching should begin, Taha Hussein’s reply was as follows: ‘It is perfectly clear that foreign languages should not be studied at this stage of general education [elementary school]: not in the first year, nor the second, nor the third, nor the fourth.’97 His justification for this was the pupil’s need to study Arabic full time, particularly in view of the major differences between the standardized language and the dialects used in everyday life. Moreover, there are great differences in grammar and pronunciation between Arabic and European languages. Taha Hussein considered that, apart from English and French, Egyptian pupils should also be able to study at least Italian and German. They would then choose one of the four as their main foreign language and another as a subsidiary.98 He also called for secondary school pupils to be taught Latin and Greek if they so desired.99 Moreover, pupils specializing in Arabic should be allowed to elect another related oriental language, particularly Farsi or Hebrew.100

Finally, Taha Hussein dealt with cultural questions, arguing that society should be converted to a written culture and that the instruments of this culture – libraries, press, media – should be promoted. He also dealt with Egypt’s cultural role in the Arab world.

Although Taha Hussein was not a specialist in education, he brought fresh ideas to this field which keep their value to the present day, while the solutions he proposed for existing educational problems were applicable not only to Egypt but to many other countries as well. That this should be so is attributable to the breadth of his experience, to his many sources of inspiration and to his involvement in public life, politics and culture in the widest sense. It is also attributable above all to his belief that education is a necessity for every human being, and to his faith in the value of knowledge and education in the life of peoples and in the building of civilizations:

The state must realize that education is as necessary to life as food and drink. Though the difference between the two is plain and simple, it is one we seldom stop to ponder. On the one hand, food and drink and everything connected with health and the body are necessities which enable man to enjoy life in just the same way as the horse, the mule, the donkey and the chicken; on the other, education is a necessity which distinguishes man from the rest of the animal world and enables him to control the rest of nature on land, in the sea and in the skies.101

Notes

1. Taha Hussein, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa fi Misr [The Future of Education in Egypt] (Vol. 9 of The Complete Works of Taha Hussein), pp. 395-6, Beirut, Dar al-Kitab al-Lubnani wa Maktab al-Madrasa, 1982. This work is regarded as the primary source for Taha Hussein’s thought on education.

2. Taha Hussein, al-Ayyam [The Days], Part 1, p. 120, Cairo, Dar al-Ma’arif, 1949.

3. His teachers included Sheikh Muhammad Abduh, one of the great innovators in Islamic thought in modern times, Sheikh Muhammad Bakhit, who was to become Mufti of Egypt, Sheikh Muhammad Mustafa al-Maraghi, who would become the Sheikh of al-Azhar, and Sheikh Sayyid al-Marsafi, who was one of the greatest influences on the boy’s personality and thought and who led him to specialize in the study of Arabic literature. Mustafa Muhammad Ahmad Rajab, The Educational Thought of Taha Hussein in Theory and Practice, pp. 5-58, Faculty of Education at Suhag, University of Assiyut, 1982 (unpublished M.A. thesis – in Arabic).

4. Abdulrahman Badawi et al., To Taha Hussein on his Seventieth Birthday, p. 10, Cairo, Dar al-Ma’arif, 1962 (in Arabic).

5. Hamdi al-Sukut and Marsden Jones, ‘Taha Hussein’, Arabic Literature in Egypt, p. 8, Vol. 1 of the series issued by the Publications Department of the American University, Cairo, 1975.

6. Badawi et al., op. cit., pp. 12-16.

7. Rajab, op. cit., pp. 19-62.

8. Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa…, op. cit., p. 11.

9. Ibid., p. 16.

10. Ibid., pp. 19-20.

11. Ibid., p. 22.

12. Ibid., p. 31.

13. Ibid., p. 21.

14. Ibid., pp. 38-9.

15. Ibid., pp. 46-7.

16. Ibid., p. 99.

17. Ibid., p. 72.

18. Ibid., pp. 72-3.

19. Ibid., p. 490.

20. Ibid., p. 492.

21. Ibid., p. 493.

22. Al-Sukut and Jones, op. cit., p. 53.

23. Hussein, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa…, op. cit., p. 51.

24. Ibid., p. 101.

25. Ibid., p. 104.

26. Ibid., p. 105.

27. Ibid., pp. 237-8.

28. Ibid., p. 12.

29. Ibid., p. 60.

30. Ibid., pp. 103-4.

31. Ibid., p. 109.

32. Ibid., p. 110.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid., p. 124.

35. Ibid., p. 122.

36. Ibid., p. 123.

37. Ibid., p. 241.

38. Ibid., p. 187.

39. Ibid., p. 241.

40. Ibid., p. 243.

41. Ibid., p. 388.

42. Ibid., p. 389.

43. Ibid., p. 390.

44. Ibid., p. 393.

45. Ibid., p. 413.

46. Ibid., pp. 414-15.

47. Ibid., pp. 411-12.

48. Ibid., p. 12.

49. Ibid., pp. 162-3.

50. Ibid., p. 239.

51. Ibid., pp. 81-2.

52. Rajab, op. cit., pp. 19-62.

53. Hussein, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa… op. cit., p. 101.

54. Ibid., p. 138.

55. Ibid., p. 139.

56. Ibid., p. 140.

57. Ibid., pp. 142-3.

58. Taha Hussein, The Bitter Truth’, article in al-Ahram, Cairo, 28 October 1949, quoted in an unpublished M.A. thesis by Kamal Hamid Ahmad Mughith, Faculty of Education, al-Azhar University, 1985, p. 201 (in Arabic).

59. Mughith, op. cit., p. 196.

60. Rajab, op. cit., pp. 159-61.

61. Hussein, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa…, op. cit., p. 151.

62. Ibid., p. 153.

63. Ibid., p. 154.

64. Ibid., p. 432.

65. Ibid., pp. 433-4.

66. Ibid., p. 164.

67. Ibid., p. 139.

68. Ibid., p. 92.

69. Ibid., p. 109.

70. Ibid., p. 169.

71. Ibid., p. 170.

72. Taha Hussein, ‘Teachers’, newspaper article in al-Jumhuriya, Cairo, 4 December 1954, quoted in Mughith, op. cit., p. 256 (in Arabic).

73. Rajab, op. cit., p. 191.

74. Hussein, Mustaqbal al-Thaqafa…, op. cit., p. 109.

75. Ibid., p. 111.

76. Ibid., p. 114.

77. Ibid., p. 127.

78. Ibid., p. 380.

79. Ibid., p. 329.

80. Ibid., p. 335.

81. Ibid., pp. 344-5.

82. Ibid.

83. Ibid., p. 384.

84. Ibid., pp. 75-100.

85. Ibid., pp. 101-8.

86. Ibid., pp. 113-14.

87. Ibid., pp. 120-4.

88. Ibid., pp. 128-35.

89. Ibid., p. 158.

90. Ibid., pp. 174-93.

91. Ibid., pp. 193-9.

92. Ibid., pp. 200-9.

93. Ibid., pp. 155-7.

94. Ibid., p. 160.

95. Ibid., pp. 210-15.

96. Ibid., pp. 216-21.

97. Ibid., pp. 245-6.

98. Ibid., pp. 251-61.

99. Ibid., pp. 262-86.

100. Ibid., pp. 287-96.

101. Ibid., pp. 234-5.

Copyright notice

This text was originally published in Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIII, no. 3/4, 1993, p. 687-710.

Reproduced with permission. For a PDF version of the article, use:

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/husseine.pdf

Photo source: Wikimedia.