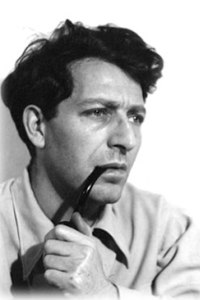

Goodman, Paul (1911-1972)

Article by Edgar Z. Friedenberg

Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown.

Paul Goodman died of a heart attack on 2 August 1972, a month short of his 61st birthday. This was not wholly unwise. He would have loathed what his country made of the 1970s and 1980s, even more than he would have enjoyed denouncing its crassness and hypocrisy. The attrition of his influence and reputation during the ensuing years would have been difficult for a figure who had longed for the recognition that had eluded him for many years, despite an extensive and varied list of publications, until Growing up absurd was published in 1960, which finally yielded him a decade of deserved renown.

It is unlikely that anything he might have published during the Reagan-Bush era could have saved him from obscurity, and from the distressing conviction that this obscurity wouldbe permanent. Those years would not have been kind to Goodman, although he was not tookind himself. He might have been and often was forgiven for this; as well as for arrogance,rudeness and a persistent, assertive homosexuality-a matter which he discusses with some pride in his 1966 memoir, Five years, which occasionally got him fired from teaching jobs. However, there was one aspect of his writing that the past two decades could not havetolerated.

Although he was often eccentrically dogmatic about most of the controversial issuesof the day that were important then, and are even more urgent now, Paul Goodman was usually right. Mainstream American thought, carrying western industrial society blithely onto ever more treacherous shoals, was wrong. Dead wrong. Goodman’s insights into the ways American society vulgarizes and perverts its institutions, especially its schools, and subverts human growth are even more valid today than when he published his ideas. Meanwhile, the resulting damage has grown more wide spread and more profound.

The world may not be able to afford to ignore Goodman any longer. Twenty years of neglect is quite enough. This profile is intended to show why his ideas deserve careful consideration and to help bring the neglect to a decent end.

Yet, it is rather astonishing that Paul Goodman should ever have commanded world attention. Looking back critically at the climate of opinion that so briefly permitted hisinfluence to flourish, it is apparent that this occurred through a kind of cultural syzygy, a rare enough condition. This is not a question of influences on Goodman’s thought, but of thechanging ideological currents that opened the minds of others. The minds that might otherwise have continued to ignore him. The right configuration of social forces did not occurtill he was nearly 50 years old; until then, he had struggled to be recognized as poet, fiction writer and intellectual force, without much success.

So, what suddenly made him a celebrity?

I believe that the single most important event that led readers to take Goodman seriously was the launching of the Soviet sputnik, the first orbiting space satellite, in 1957.I do not mean that this triumph greatly impressed Goodman, though he did become enthusiastic about the programs that succeeded in landing three relatively harmless persons on the moon just two years before his death. But the sputnik impressed the American people.

It terrified them into scrutinizing American education as the probable cause of deficiencies inAmerican technical and scientific competence. This, in turn, required that they interestthemselves in what might be happening to American youth. In Growing up absurd, Pau lGoodman was more than eager to tell them this. In the Preface to that work, he observed:

The present widespread concern about education is only superficially a part of the Cold War, the need to matchthe Russian scientists. For in the discussions, pretty soon it becomes clear that people are uneasy about, ashamedof, the world that they have given their children to grow up in. That world is not manly enough; it is not earnest enough; a grown up may be cynical (or resigned) about his own convenient adjustments, but he is by no means willing to see his children robbed of a worthwhile society (1960, p. xv).

This, in view of American fiscal policy since Goodman wrote, seems too generous. American views of young people are variable and complex, but some prevalent attitudes are quitestable, conspicuous, and influential. They are not very favourable. On the familiar evidenceof so many sexy TV commercials, ‘teen’ movies, and rejuvenating cosmetic operations, Americans are widely believed to worship youth. More often, however, they covet youth, andcovetousness does not dispose us to affection.

Adults who consider youth seriously are expected to view young people with detachment, as problems or sources of problems. To approach them respectfully as humanbeings with their own lives to lead and their own selves to govern arouses suspicion even inthe young people themselves, who cannot imagine, or imagine all too vividly, what a welldisposedadult might want from them.

Sputnikangst did not change all that. Today, intergenerational hostility remains moreintense than ever throughout the world, and it reels from folly to folly as hysteria seizes on alleged instances of drug abuse and child abuse, with much attention to which is which. But Sputnikangst did breach a wall of adult indifference about youth and it provided a temporaryopening for Goodman’s concern for the plight of boys and young men in American society.

Goodman was forthright in acknowledging that his interests were asymmetric with respect to gender; and he had no problem justifying his neglect of girls in his book. Today,his politically incorrect explanation seems both offensive and implausible; but it is not illogical.

The problems I want to discuss in this book belong primarily, in our society, to the boys: how to be useful andmake something of oneself. A girl does not have to, she is not expected to `make something’ of herself. Her career does not have to be self-justifying, for she will have children, which is absolutely self-justifying, like anyother natural or creative act. With this background, it is less important, for instance, what job an average young woman works at till she is married. The quest for the glamour jobs is given at least a little substance by its relation to a ‘better’ marriage (1960, p. 13).

So much for girls in Growing up absurd. Boys, however, face a lifetime of meaningless work at tasks they do not select and are not free to reject, which provide them with neither autonomy nor security, and which undermine their self-respect. Repeatedly and poignantly, Goodman laments the dearth of opportunity for ‘manly work’. Those who choose or who are forced into the paths of juvenile delinquency may, indeed, find more challenge, though at enormous risk to their ultimate development.

Goodman’s intense need to build and share communities with virile young menstrongly influenced all his writing, as he proudly acknowledged. His preoccupations withboys and images of boys marred much of his fiction and poetry, which he often allowed to become so self-indulgent that the characters in them seem merely reflections of what he would like to have been himself. But his sexuality was a great asset to him in Growing up absurd.

I feel qualified to make such an assessment: my own book, The vanishing adolescent,published in 1959, was also devoted, in every sense, to boys. The two books were often confused. In the 1960s, several people I met congratulated me by telling me how much they had enjoyed reading Growing up absurd and I would assure them, sincerely, that I had too.

Although gender equality had not yet attained its present moral authority, some readers and reviewers reproached me for my bias and neglect of young women. I was notgreatly troubled by this criticism. I believed, then as now, that a writer has a right and,indeed, a duty to write only about things and people he knows and cares about-one way oranother. A less limited person might have written a better book; but my book would not havebeen improved by attempts to extend it beyond my emotional range. Goodman doubtlessagreed; we both used homosexuality as a talisman to permit us to write lovingly about youngmen without troubling to find some instrumental justification. Readers seized on Growing Up Absurd as a book about education and the need for school-indeed social-reform. How else could they have accepted it?

Goodman clearly intended Growing up absurd to have a practical and beneficial influence on school and society. Yet what gives the book its strength is its unabashedconviction and assertion that boys are to be treasured and nurtured rather than, as so often happens, crippled and distorted to make them useful to others in the social roles for which they are to be prepared. Conversely: it is society’s obligation to provide them with the meansto develop into decent citizens and members of a caring and productive community.

If Sputnikangst helped make adults listen seriously to men who treasured boys, there were certain other factors in the social climate of the day that made it more receptive to Goodman’s message. Climates are changeable, which may make them propitious at certain transitional points. Today, Growing up absurd would be unlikely to survive the derision of women justly critical of Goodman’s literally cavalier neglect of them. But if it had appeared afew years earlier, the book would have been rejected because of its acceptance of adolescentsexuality itself-not just homosexuality, which is briefly and rather pedantically discussed in Growing up absurd (1960, p. 127-29) but exuberant sexuality in general.

By the mid-1950s Goodman’s hour had come round at last. The prevailing ‘squeaky clean’ image of American youth was under attack and was being relinquished by a filmindustry increasingly dependent on the patronage of youth. In 1955 the young actor, James Dean, whose image might have been designed to win Goodman’s heart, was killed in anautomobile accident at the age of 24. This was the same year the two films that made Dean anicon as well as a falling star, East of Eden and Rebel without a cause, were released. The immortal Elvis Presley’s first hit-movie Love me tender appeared in 1956. Clearly, the timewas ripe for movies and books that celebrated the sexuality of adolescent males.Goodman’s interests were, however, sharply focussed and narrowed by his strong and rather exceptional social values, political commitments, and preference in what we wouldnow call ‘lifestyles’. The changing political climate of the 1960s, at first supportive, becameproblematic. He admired what he and Norman Mailer called ‘hipsters’ (as distinct from theirsuccessors, ‘hippies’: flower children not tough enough for him-especially intellectually-and who tended to adopt rural lifestyles disconcerting to this inveterate New Yorker).

Hipsters do not drop out; they establish themselves in the nooks and crannies ofsociety as gamesmen and tricksters. They get along. Horatio, the picaresque young hero ofGoodman’s enormous phantasmagoric novel, The empire city, revised and published piecemeal from 1942 to 1959, might be regarded as the archetype of the hipster.

If sexuality provided one focus of Goodman’s hyperbolic discourse, the other was surely provided by community. Communitas: means of livelihood and ways of life, written in collaboration with and illustrated by his architect-brother Percival, is arguably his best book.Published in 1949 and revised in 1960, it has become a landmark in the literature of city planning, rather like the better-remembered work of Lewis Mumford, whose influence itshows. Communitas is far more than a treatise on the problems of urban development. It is amoral discourse rooted in the issues city dwellers in a modern industrial society confront orfail to confront; and illustrated with concrete proposals for the design and construction of a metropolis in which civility might develop and be maintained.

This interest continued to inform Goodman’s work for the rest of his life, extending tothe broadest issues of national policy. Consider the mere titles of some of his later essays:Utopian essays and practical proposals (1962a); The society I live in is mine (1963); People or personnel (1965). Perhaps, paradoxically, it both dated him and made him prophetic. It dated him because American interest in community tends to be superficial and nostalgic. To the creators and distributors of Disneyland, Disneyworld, and Eurodisney, a concern for genuine community may seem embarrassingly old-fashioned. Yet this very concern underlies Goodman’s continued critique of American society as mercenary, impersonal, destructive ofpersonal intercourse and fidelity, and of the natural order as well. The effects of these catabolic social processes on youth was the subject of Growing up absurd; but Goodman continued to analyze and decry their influence on all aspects of society for the rest of his life;abandoning the literacy forms that had previously constituted his oeuvre. He could hardly have found the time or the privacy to continue to write fiction. For the next and final decadeof his life he was in too much demand as a public figure.

The decay of community and the consequent destruction of the quality of Americanlife have now become so familiar as to arouse more cynicism than anger. Goodman wasangry for most of his life; but he was quite incapable of cynicism. His personality was tooold-fashioned for that. He frequently referred to himself as ‘a man of letters in the old fashioned sense’, disclaiming rather scornfully the identity of a social scientist that was often thrust upon him. In fact, Goodman was even more old-fashioned than that.

Throughout his difficult and often troubled life, and most insistently towards the endwhen he could count on some attention being paid, Paul Goodman was an American patriot. As such, he was necessarily a highly articulate opponent of American foreign policy in the Viet Nam War.

In retrospect, it seems rather curious that a man, who so articulately attacked the corevalues of a nation-State, notorious at the time for its ill treatment of political dissent, shouldhave been spared public and official attack. Why wasn’t Goodman attacked and destroyedearly on as a subversive? This is an interesting question. Goodman’s unusual politicalposition made him peculiarly suited to pass unscathed through the window of opportunitythat ultimately opened for him and that probably no longer exists.

As Kingsley Widmer observes in his sometimes scathing but perceptive study:

In several ways it is odd that Goodman became an avowed anarchist in the mid-1940s. He showed little interestin libertarianism, or even in much of what was then called `social conscience’, in his student days, in histwenties, and in most of his writings. He was not in most usual senses a rebellious character as a student-farless than most who became anarchists. His anxious and defensive self-conceit, his petty-bourgeois origins, hisnarrow worldly experience and confinement to a New York lumpen-intellectual milieu, his insistent role-playingas Artist and Man of Letters, his lack of concern with most issues of equality and justice-these hardlyencourage the styles of the great rebel or revolutionary (Widmer, 1980).

Character and attitudes such as these, if less repellent than Widmer makes them sound, would certainly have served to make Goodman less vulnerable to the attacks on left-wing expression that silenced so many American intellectuals during his active life. He seldom became heavily involved in groups he could not dominate, which limited him to becoming at most acult figure. The cults in which he figured were not explicitly political and they did not seekpower as such. As opposition to intervention by the United States in Southeast Asia intensified, particularly with regard to the ways in which universities supported the war effort, student activists turned increasingly to Goodman as one of the few intellectuals overthe age of 30 whom they could trust; many worshipped him and he gloried in their admiration and welcomed their intimacy.

But he became a harsh critic of student activists and occasionally their opponent as they mounted their attack not only on universities as tools of national policy, but also on thevery idea of the university and of scholarship itself. He deplored their conviction that ignorance is to be cherished as a virtue and their eagerness to learn nothing from history. Healso disliked coercive violence; Goodman endorsed violence such as fistfights as an unambiguous expression of feelings that cleared the air and resolved tension. However the penultimate days of the 1960s student revolt, like the war itself, repelled him.

Surprisingly, Goodman did not show much interest in political activity. Despite his emphasis on the value of community, he displayed and aspired to few political skills. He was not sufficiently interested in other people, even to manipulate them effectively over a long period of time. Before his death Goodman had, in effect, abandoned the student left-wing, although he remains one of its memorable figures.

While many of his contemporaries, who shared his social values, devoted their energyto action that brought them to the unfavourable attention of the authorities, Goodman devoted his energy to his career. He struggled to become recognized as an established academic formost of his life; although much he was popular a visiting lecturer after Growing up Absurd was published. He never received a conventional, tenured, academic appointment. He became a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1936, survived in the ‘Second City’ forfour years before returning to New York, and resided there for the rest of his life. Eighteen years later, he completed his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Chicago. It was publishedas The structure of literature by the University of Chicago Press in 1954. This seems an unpromising record for a revolutionary social critic. Yet, as an author Goodman ratheradmired once observed, ‘Sweet are the uses of adversity which like the toad, ugly and venomous, bears yet a precious jewel in its head’ (Shakespeare, As you like it). The same might, on occasion, have been said of Goodman himself. However his earlier protracted exemption from public haunts certainly served to protect and preserve him for later, invaluable service; as did his 1944 draft deferment and rejection.

Two other important Leitmotive, that recurred throughout Goodman’s statements and placed him conspicuously in the limelight of contemporary controversies, would, however,limit his influence today: his attitudes toward the authority of science and toward psychotherapy. He supported both enthusiastically. In the 1950s these were positions thatrather sharply defined one’s place on the spectrum of enlightened opinion.

Then as now, the general public accepted science as the arbiter of truth and the source of progress. However, after the atomic bombing of Japan and the testing of the hydrogenbomb, even mainstream thought and certainly progressive intellectuals became wary of the sinister possibilities of scientific development and of the uses to which governments mightput it. A self-proclaimed anarchist might have been expected to share these trepidations moststrongly; but Goodman, though an active and dedicated opponent of American belligerence,did not see the uses to which institutionalized science lends itself as implicit in the nature ofscientific endeavour itself.

Paradoxically, Goodman’s confidence in the beneficent promise of science confirms Lord Snow’s famous complaint that the profound and mutual ignorance of the ‘two cultures’-scientists and humanists-jeopardizes the society they share with all of us. Few scientists could have been quite so uncritical of the limitations of their own discipline. But asa former student and disciple of Richard McKeon trained in philosophy at Columbia and the University of Chicago, Goodman should have been more skeptical of the scientific method as6an epistemological instrument. And certainly after 1962 when Thomas Kuhn’s epoch-making The structure of scientific revolutions was published and most of Goodman’s most influential decade still lay before him, any serious scholar should have become aware that scientific knowledge, like all knowledge, was inherently ideological and contingent on the politics ofits discipline. Goodman continued to hope against hope, however, that it might serve theworld as deus ex machina. This, like his patriotism and of a piece with it, tends to obscure the continued validity of his more fundamental contributions to social thought, making his work look naive and imperfect.

Again paradoxically, the ideas about human feeling and thought that informed Goodman’s work, including his early adherence to the Dionysian doctrines of Wilhelm Reichand his later practice of gestalt therapy as a lay analyst, were strongly and often sardonically anti-scientific. The paradox probably never troubled him, since his objections to a scientific approach to psychotherapy were not directed against the conventions of scientific method, but rather against treating human emotion and behaviour as phenomena that could best beanalyzed coolly apart from the contexts in which they occurred. Gestalt therapy, asformulated by Fritz and Lore Perls, with whom Goodman worked, was not a researchtechnique. Theoretically, it was a miscellany and proud of it: the predecessor of the‘encounter-group’ and ‘primal scream’ procedures that became fashionable a few years later.It was, however, 1951 when Goodman collaborated with Perls on volume two of Gestalt therapy. In a passage from the book Goodman asserts that patients who surrender to gestalt therapy are helped:

by finally ‘standing out of the way’, to quote the great formula of Tao. They disengage from their preconceptions of how it ‘ought’ to turn out. And into the ‘fertile void’ thus formed, the solution comes flooding(Perls, et al., 1951, p. 358 59).

But the basic approach is illustrated in an earlier passage:

The only useful method of argument is to bring into the picture the total context of the problem, including the conditions of experiencing it, the social milieu and the personal ‘defenses’ of the observer. That is, to subject the opinion and his holding of it to gestalt-analysis … we are sensible that this is a development of the argument adhominem, only much more offensive, for we not only call our opponent a rascal and therefore in error, but we also charitably assist him to mend his ways! (ibid., p. 243).

Tao? It sounds a lot more like Mao. And, having observed one gestalt therapy session at Goodman’s invitation, I can confirm that it looked and felt that way too. Both Mao and Laotzuhad a strong appeal to dissenting youth in the 1960s; and both had something useful and unfamiliar to contribute to their understanding, and ours, of what is wrong with the world welive in. Yet Goodman was, indeed, neither a Maoist nor a Taoist; he seems to have been a bitof a Manichaean, and that has made his thought biodegradable. If those views on the care and nurture of the human psyche that appealed to counter cultural youth then seem repellently atavistic today, it is not so much because their specific content is obsolete but because the prevailing attitude toward all schools of psychotherapy have changed. Like science, psychotherapy now seems neither a promising instrument ofliberation or necessarily of oppression; though it can be and often is effectively used foreither purpose. More fundamentally, both are epiphenomena of modern industrial societyand, as such, cannot be innocent of their abuses. We take them for what they are worth, paymore for their prospective benefits than we can possibly afford, and worry, with good reason,about the consequences. Lao-tzu did give warning, though, that to those who seek to seize thegood while rejecting the evil, as Goodman consistently did, evil returns with redoubledstrength.

The common factor underlying Goodman’s faith in the authority of science and the effectiveness of psychotherapy, that has now become much less acceptable, is his commitment to intrusiveness: i.e. confident technical intervention into conditions and processes he found deplorable. This has changed, though probably not permanently, in the past twenty years. Partly in response to the Viet Nam fiasco, even Americans have come to understand that good intentions are no guarantee of good results, and no justification formeddling forcefully in situations that you may not understand as well as you think you do.Neither Goodman nor I, of course, would agree that our intentions in Indochina were good, so this seems a rather limited insight. However, even though this falls far short of truerepentance, it is sometimes enough to temper current responses to reformist zeal.

Today, Goodman’s hectoring tone seems offensively optimistic. Most of the abuses heattacked are too deeply rooted in our culture and our economy to be eradicated withoutrisking its destruction: a hazardous and thank less, though necessary, undertaking. Perceptive and prescient as he clearly was, his approach to problems and his rhetoric now seem selfindulgent,imprecise and, curiously, both streetwise and naive. In a word, perhaps,adolescent-a word Goodman would surely have recognized as a compliment.

Three books about education

In the preceding section of this profile, I have discussed how the most salient convictions andissues that pervade Paul Goodman’s work were affected by the social climate in which helived, and how that social climate determined the way his work was received. In doing this Ihave made his development and his place in society to appear more coherent than, in fact,they could have been. However, I have not explained how an extremely prolific author whodid not address questions of education until the final decade of his 60 years should have earned so prominent a place among critics of schooling.

Goodman’s life was in fact more coherent than his reputation would suggest. Onecould hardly have expected, considering the sexual orientation that coloured his work andthat he proclaimed publicly long before most gay men thought it prudent, that Goodmanwould have lived, consecutively, with two women for most of his adult life. The first, Virginia Miller, whom lived with him for five years, bore him a daughter. The second, Sally Duchsten, bore him a son and a daughter seventeen years apart. The couple lived together fortwenty-seven years until Goodman’s death.

Despite his evident delight in the role of iconoclast and anarchist, his family was theheart of his emotional commitment. His son Matthew’s clear-eyed, humorous affection forhis father was apparent to anyone who knew him. It was mutual, certainly. Matthew waskilled in a mountaineering accident in 1967, shortly before his 21st birthday. Though he was not there at the time, the tragedy also ended Paul’s life, though it took five years to do it.

Though Goodman sometimes gloried in promiscuity, he was largely incapable of infidelity. Moreover, although he wrote in every conceivable genre-poetry, plays, novels,short stories, literary and social criticism-his oeuvre is coherent, even, indeed, repetitious. In some of these forms-plays especially and sometimes poetry-he wrote very badly; andhis best work was often angrily polemical and none the worse for that. Taken at a whole, however, it is remarkably faithful to the values and issues that concerned Goodman deeply.

Yet, the reception accorded to Growing up absurd marked a change in the nature of Goodman’s output. He no longer published works like the essays his friend Taylor Stoehr collected and published posthumously under the title Nature heals: the psychological essays of Paul Goodman (Stoehr, 1977) and Gestalt therapy (Perls et al., 1951). He no longer produced the short stories that he had previously written so prolifically, four volumes ofwhich Stoehr would also collect and publish after Goodman’s death (Stoehr, 1980).

Growing up absurd marks an intellectual divide between Goodman’s earlier, largely forgotten literary and philosophical writing and his later polemical writing on issues of publicpolicy, especially education, which seems more pertinent than ever. What brought thischange about? Did Goodman’s interests suddenly alter? That depends on what is meant by‘interests’. On the whole, however, the answer is ‘no’.

It was certainly in Goodman’s interest to exploit the opportunity so to reach the wider audience that fame had brought him. For the first time in his 50 years, he and his family enjoyed a decent income. Interest in his fiction also revived; The empire city (1959) and the short stories attracted renewed interest and were reprinted. Yet only by continuing to develop the kind of social criticism manifested in Growing up absurd could he continue to meet and foster the growth of the demands now being made on him as a public speaker, reaching their summit perhaps in an invitation to deliver the prestigious Massey Lectures for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation on ‘The Moral Ambiguity of America’ in 1966 (Like a conqueredprovince, 1967), and as a contributor to major American journals of opinion.

Critics disagree as to whether Growing up absurd is Goodman’s best book; but there can be no doubt that it became the most influential. Why is this? Why did it lead to hisbecoming recognized as a leading authority on education?

Goodman does not really have that much to say about schools as such in Growing up absurd; that came later in Compulsory miseducation (1964). Growing up absurd provided him with a forum from which to address the issues of sexuality, community, and thetruncation of emotional and intellectual development that had concerned him all his life. However, people in industrial societies relate youth to school children; during school hours itis illegal for them to be anywhere else. Among the prevailing assumptions about schools is that they prepare pupils for useful employment and successful careers, and are designed tofurther their development; that schools should discipline their exuberant sexuality; that school is where they belong and is the right place for them to be-at worst, it keeps the kids off the streets. Rejection of schooling is a serious social problem which readers expected Growingup absurd to help them solve.Goodman rejected all of these assumptions. He insisted that serious improvement ineducation, as in life, could only be achieved by fundamental restructuring of society itself.

For it can be shown-I intend to show-that . . . our abundant society is at present simply deficient in many ofthe most elementary objective opportunities and worthwhile goals that could make growing up possible. It is lacking in enough man’s work. It is lacking in honest public speech, and people are not taken seriously. It thwarts aptitude and creates stupidity. It corrupts ingenuous patriotism. It corrupts the fine arts. It shack less cience. It dampens animal ardour. It discourages the religious convictions of Justification and Vocation and itdims the sense that there is a Creation. It has no Honour. It has no Community.

Just look at that list. There is nothing in it that is surprising, in either the small letters or the capitals. Ihave nothing subtle or novel to say in this book; these are the things that everybody knows (1960, p. 12).

Well, yes. Isn’t that what society is supposed to do? Civilization has its discontents.

As to jobs and careers; Goodman regards these as crucially important-how could henot? The first chapter in Growing up absurd deals with and is entitled ‘Jobs’: the school’srole in preparing pupils to acquire them.

For the uneducated there will be no jobs at all. This is humanly most unfortunate, for presumably those whohave learned something in schools, and have the knack of surviving the boredom of those schools, could also make something of idleness; whereas the uneducated are useless at leisure too. It takes application, a fine senseof value, and a powerful community-spirit for a people to have serious leisure, and this has not been the geniusof the Americans.

From this point of view, we can sympathetically understand the pathos of our American school policy,which otherwise seems so inexplicable; at great expense compelling kids to go to school who do not want it and who will not profit by it. There are, of course, unpedagogic motives, like relieving the home, controlling delinquency, and keeping kids from competing for jobs. But there is also this desperately earnest pedagogicmotive of preparing the kids to take some part in a democratic society that does not need them. Otherwise, whatwill become of them if they don’t know anything?

Compulsory public education spread universally during the nineteenth century to provide the reading,writing, and arithmetic necessary to build a modern industrial economy. With the overmaturity of the economy, the teachers are struggling to preserve the elementary system when the economy no longer requires it and isstingy about paying for it. The demand is for scientists and technicians, the 15 per cent of the `academically talented’ (1960, p. 32-33).

For Goodman, who was an admirer of John Dewey, who so strongly believed that schooling must be rooted in personal experience and community life, the schools are part of the problem. As components of what he calls ‘the organized system’ they cannot contribute much to the solution. Growing up absurd is devoted to an indictment of that system, category by category, for its baleful influence on ‘Class Structure’, ‘Aptitude’, ‘Patriotism’ and ‘Faith’: these are some of the chapter headings. In a final chapter, ‘The Missing Community’,Goodman sums up in some detail ‘the missed revolutions of modern times-the fallings-short and the compromises-that add up to the conditions that make it hard for the young to grow up in our society’ (italics Goodman’s, 1960, p. 231). If his diagnoses no longer astonish, it is because, in the thirty-two years since he made them, there has been so little improvement despite much technological and superficial political change.

As an anarchist, Goodman could hardly have been required to present and advocate a systematic program for social change. Nor does he. It is his anarchy, rather than his genuine patriotism, that saved him from being condemned as a subversive. Having no great expectations of the State, he made no doctrinaire demands for fundamental change. He was alibertarian, not a socialist. You can’t be more American than that!

Four years after Growing up absurd, Goodman published a book dealing specificallywith education entitled Compulsory miseducation (1964). The book is essentially a shorter sequel to Growing up absurd, but it provides a more manageable source for readers primarily interested in Goodman’s thought about education.

Unlike Growing up absurd, Compulsory miseducation offers a multi-pronged critiqueof schooling, and provocative programs for improving education at the elementary, secondaryand college level. These are less often directed at improving schooling than at enabling learners to escape and find alternatives to the schools that might enhance rather than impairtheir prospects for education.

It is in the schools and from the mass media, rather than at home or from their friends, that the mass of ourcitizens in all classes learn that life is inevitably routine, depersonalized, venally graded; that it is best to toe the mark and shut up; that there is no place for spontaneity, open sexuality, free spirit. Trained in the schools, theygo on to the same quality of jobs, culture, politics. This is education, mis-education, socializing to the nationalnorms and regimenting to the national `needs’ (1964, p. 23).

Asserting that `the compulsory system has become a universal trap and it is no good’ (p. 31), Goodman presents six alternative proposals:

1. Have ‘no school at all’ for a few classes. These children should be selected from tolerable, though not necessarily cultured homes. They should be neighbours and numerous enough to be a society for one another and so that they do not feel merely ‘different’. This experiment cannot do the children anyacademic harm, since there is good evidence that normal children will make up the first seven years school-work with four to seven years of good teaching.

2. Dispense with the school building for a few classes; provide teachers and use the city itself as theschool-its streets, cafeterias, stores, movies, museums, parks and factories.

3. Use appropriate unlicensed adults of the community-the druggist, the store keeper, the mechanic-asthe proper educators of the young into the grown-up world. Certainly it would be a useful andanimating experience for the adults.

4. Make class attendance not compulsory, in the manner of A.S. Neill’s Summerhill. If the teachers aregood, absence would tend to be eliminated; if they are bad, let them know it. The compulsory law isuseful in getting the children away from their parents, but it must not result in trapping the children.

5. Decentralize an urban school (or do not build a new big building) into small units, 20 to 50, in available store fronts or club houses. These tiny schools, equipped with record-player and pin-ball machines,could combine play, socializing, discussion, and formal teaching. For special events, the small unitscan be brought together into a common auditorium or gymnasium, so as to give the sense of the greater community.

6. Use a pro-rata part of the school money to send children to economically marginal farms for a coupleof months a year, perhaps six children from mixed backgrounds to a farmer. The only requirement is that the farmer feed them and not beat them; best, of course, if they take part in the farm work.

Above all, we must apply these or any other proposals to particular individuals and small groups, without the obligation of uniformity. There is a case for uniform standards of achievement, lodged in the Regents [the NewYork State Education Authority] but they cannot be achieved by uniform techniques (1964, p. 32-34).

In retrospect, these suggestions, though sincerely offered, do not seem quite serious efforts tocorrect the deficiencies of schooling Goodman attacked. He was obliged to offer them;critics, especially in America, are expected to tell their readers how to correct the abuses theydeplore. Goodmam, moreover, was ambivalent about his status as an intellectual and wantedbadly to be regarded as a practical man. I can recall him reporting indignantly on the reaction of some broadcasting executives who had invited him to take part in a panel on the influence of sponsors on program content. In those days, programs were associated with individual sponsors who frequently interfered directly in program planning; and Goodman suggested instead that they be permitted to buy time for their commercial messages as they doadvertising space in periodicals, rather than identify themselves as ‘the company that brings you’ whatever.

This, of course, is the way television is financed today; but Goodman reported that theexecutives were infuriated by his attempt to help them solve the problem. ‘We expected youto attack our programming as dreadful’, they explained, ‘but it’s inevitable so! We didn’t expect you to try to tell us how to run our business.’ Goodman published this account, but I am daunted by the task of finding the quote among his mass of publications, and I did hear him tell this story myself. Often.

Throughout his work, Goodman complained that nothing would actually be done tocorrect the things he complained about since, whatever they were, they reflectedestablishment policy or they would not have occurred in the first place. In fact, hissuggestions came to be widely adopted, though in piecemeal and diminished form. Somewere assimilated into established practice, like taking pupils out into the city itself which expanded from the conventional field trip into a much more comprehensive interaction of the kind Goodman described, initiated by an innovative school superintendent in Philadelphia. Respected mainstream practitioners like Theodore Sizer, in his influential books Horace’s compromise (1984) and Horace’s school (1992), recommended dividing large, impersonal schools into smaller units, each with its own faculty, though he would design a much more academic curriculum than Goodman. Sizer’s plan is now being explored in practice by some 200 members of the Coalition of Essential Schools, formed in 1984. (Sizer, 1992, p. 207 etseq.)

Conversely, several of the educational practices Goodman condemns in Compulsory miseducation have been either abandoned or assimilated beyond recognition. It is difficulteven to remember now just what was meant by ‘programmed instruction’: the fad of‘teaching machines’ to which Goodman devoted his entire Chapter 6 (1964, p. 80-91).Computers have become less conspicuous but more ubiquitous in schooling, as in real life while the threat of depersonalization and diminution of the teacher’s role has been even morefully realized by institutional than by technological means.

The de-skilling of the teaching profession, which has been the subject of much ofMichael Apple’s (1979) brilliant work is being accomplished by prescription rather than bymechanization, with published teacher’s guides scripting permissible uses of materials. The centralization of curriculum construction and the penalties incurred by teachers who expandon the materials provided has gone much further than Goodman could have imagined, andnot only or even primarily in the United States. James Meikle (1992) reports recent tightening of national control over education in the United Kingdom where ‘a compulsory canon of great works’ will also be introduced on the advice of the National Curriculum Council, whose recommendations were welcomed by John Patten, the Education Secretary. He also ordered that for the next three years all 14-year-olds must face tests in one of Shakespere’s plays. A midsummer night’s dream, Romeo and juliet, and Julius caesar. In the recommendations, David Pascall, the former Downing Street adviser who chairs the National Curriculum Council, suggested that teachers should sensitively correct pupils who speak sloppily in playgrounds. ‘English is the most important national curriculum subject’, he said. ‘It provides the foundation for all future learning and for success in life.’ Nearly thirty years earlier, Goodman had observed:

Speech cannot be personal and poetic when there is embarrassment of self-revelation, including revelation tooneself, nor when there is animal diffidence and communal suspicion, shame of exhibition and eccentricity,clinging to social norms. Speech cannot be initiating when the chief social institutions are bureaucratized andpredetermine all procedures and decisions, so that in fact individuals have no power anyway that is useful toexpress.Speech cannot be exploratory and heuristic when pervasive chronic anxiety keeps people from risking losing themselves in temporary confusion and from relying for help precisely on communicating, even if the communication is Babel (1964, p. 79).

Appropriate as it clearly was for Goodman to offer useful suggestions for improving thequality of schooling, I find that they weaken his work. Its main strength lies in the clarity ofthe moral and civic vision on which he based his criticism of the school and the society ofwhich they were a part, and whose instrument they were and continue to be. It is disturbing tofind him, nevertheless, so ready to help make the best of a bad job; though, for the student’ssake, one has to try. Thirty years later, it is apparent that many of the suggestions he offered have indeed been adopted as customary practice; and that, indeed, they have not made much difference after all.

As the whole tenor of Goodman’s discussion shows, effective improvements inschooling depend upon drastic improvement in the social and political status of youth. They have been waiting a long time. The third and final section of Compulsory miseducation is devoted to a discussion of college education. Goodman initially emphasizes the unsuitabilityof academic education for many young people who feel compelled to go to college for thesake of their economic future, and to which, in any case, college may offer little that isrelevant. One of his persistent concerns in much of his work, which the experience of young dropouts in the 1960s reinforced, is the extreme difficulty of managing a life of stable, decentpoverty outside the rat-race. Goodman offers ‘Two Simple Proposals’ (1964, p. 124-30) to make college more meaningful and accessible. The first is that:

half a dozen of the most prestigious liberal arts colleges . . . would announce that, beginning in 1966, they required for admission a two-year period, after high school, spent in some maturing activity . . . The purpose ofthis proposal is two fold: to get students with enough life experience to be educable on the college level . . . and to break the lockstep of twelve years of doing assigned lessons for grades, so that the student may approach hiscollege studies with some intrinsic motivation, and therefore perhaps assimilate something that might changehim.

The second even simpler proposal is that grading be abolished and testing used, albeit more extensively, for diagnostic purposes in guiding teaching. Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts, has, in effect, done this; though students still must ultimately write acceptable dissertations in order to graduate.

It is not that simple, as Goodman must have known. This section of Compulsorymiseducation dealing with college seems to be tacked on, digested from the work Goodman published in 1962, The community of scholars. Much of the book is devoted to a casually presented history of universities from medieval times, intended to define their essential natureand judge how much of that may still be rescued from the ravages of bureaucratization. The book is sensible and, for its time, highly perceptive. Goodman, moreover, was about the onlyleft-leaning critic of education who wrote with respect for and commitment to classical learning; as, indeed, ‘a man of letters in the old fashioned sense’ though prideful of the letters‘Ph.D.’. Still, The Community of Scholars now seems a bit peculiar, like a treatise oncetology written by Jonah.

Goodman’s place among critics of education: then and now

In 1967, the journalist and social critic, Peter Schrag, published an article in Saturday review in which he summarized and appraised the critique of schooling that a number of us withsomewhat similar perspectives had generated during the previous decade. Besides Goodmanand myself, Schrag included George Dennison, John Holt, Herbert Kohl and Jonathon Kozol,among others. James Herndon, the most perceptive of us all, as well as the only who had beenand was to remain a public school-teacher all his working life, had not yet published The wayit spozed to be (1968), the first of a series of books that still provide the best account I know of how schools-in this case in Northern California-really operate from day to day.

Schrag called us ‘Education’s Romantic Critics’, by which he meant that our warm concern for school children was admirable but our political demands on schools were unrealistic. But in the 1960s, in the United States of America, cultural conflict was pervasive and intense enough to suggest that, though politics may be the art of the possible, that art wasgetting more expressionistic. We were a part of the movement: Archimedes searching fortenure.

Although we recognized one another as peers who shared many common values that were poorly served in schools, there were significant differences among us. George Dennison founded the First Street School on Manhattan’s lower east side in the autumn of 1964, with a group of twenty-three kids, mostly poor, with whom the public schools had failed. Their only common feature at the outset was their detestation of and distrust for the schooling that had branded them as failures. The school was brought to an abrupt demise at the end of the schoolyear by its own success. When it ran out of money, it was refused foundation grants on the grounds that, having proved itself successful, it was ineligible as an experimental school. Dennison described the school and its pupils in The lives of children (1969), perhaps the best written and most moving book any of us had written.

Though he trained with Paul Goodman at the Institute for Gestalt Therapy and quotes from him favourably in the lives of children, Dennison’s work reveals, by comparison,Goodman’s sentimentality. Dennison’s pupils do use the city as their classroom, often driving him beyond exasperation by their extramural behaviour:

By this time I was thoroughly disgusted with all of them, their incessant screaming, their violence, their fearfulness, their shallow, wretched personalities, their superstitions, their worship of Cadillacs and crooks, their stupid fantasies, their impatience, their emptiness. I turned around without a word and walked away, fully intending to abandon them and go home (Dennison, 1969, p. 145).

Oh, sure, Jose, the saturnine young Puerto Rican whom Dennison virtually nurses back to literacy after the New York City schools had driven the native language he had read andwritten fluently out of his mind, contrasts sharply with Goodman’s wish-fulfilment: Horatio, the fantastic adolescent Latino hero of The empire city (1959). Still, Goodman was correct inwanting to send some of the city kids he loved for a respite on a farm like Dennison’s; and Dennison, I believe, would have welcomed them to the farm in Maine where he spent hislater life as a distinguished novelist.

John Holt, one of Dennison’s closest friends, was also totally unlike Goodman. Holtwas a cool man; a U.S. Navy submarine commander during the Second World War and a mathematics teacher. His first book and the one that made him famous, How children fail(1967), originated in Holt’s curiosity about the intellectual miscarriages that make it impossible for some children to learn simple arithmetic. Careful observation revealed to himthat they were usually preoccupied with quite a different problem: figuring out from herbehaviour what answer the teacher wanted; they weren’t thinking about mathematics at all.

Even today, people often misquote the title of Holt’s book as `Why children fail?’: but Holt was never that clinical: he meant ‘how’, not ‘why’; and as soon as he understood ‘how’,‘why’ was obvious. Schools ran on competition and anxiety, and the children understood quite well what was actually demanded of them and that failure must be avoided at whatevercost to what they might otherwise have learned. Holt came quickly to share, perhaps he even surpassed, Goodman’s loathing and contempt for institutionalized schooling as an obstacle to education. As a lifelong bachelor, I think he prized children as people more than any of usand had an uncanny rapport with them.

He and Goodman could not have been less similar: Goodman the quintessential NewYork Jew, a seductive lecturer at once casual and pretentious. Holt was midwestern born and Colorado bred, also casual but a dull and simple lecturer whose audience and readersunderstood exactly what he meant. What they did have in common was an interest in local,community politics; to which they brought contrasting emphases. Goodman was an ideologue for community; Holt a quiet technician increasingly skilled at showing parents how to gettheir kids out of the organized system Goodman so stridently condemned. He organized anetwork of correspondents throughout North America and beyond with a newsletter through which parents could keep one another informed about their progress and problems in organizing small, independent schools or home schooling for their kids. Still, he had very little interest in the broader issues of politics, and never seriously addressed the segregation is timplications of his approach to deschooling, which would certainly and properly have troubled Goodman. He wrote several books after How children fail, some intended to suggest to teachers ways they might improve their instruction, but increasingly devoted to getting children out of formal schools altogether, like Teach your own: a hopeful path for education (1981).

Herbert Kohl and Jonathon Kozol, both former Harvard undergraduates, began by focusing their attention on the difficulties in the slums and, especially, the problems black children encounter in schooling. Their approach contrasts with that of Herndon who, equallyrespectful of such pupils as human beings, writes of them as equals with a sardonic appreciation for their strategies in dealing with schools that can be a lot dumber than they are. Kohl’s 36 children (1967) is an account of his poignant experiences in teaching English and,especially, poetry to classes of Harlem schoolchildren who often developed real poetic gifts, only to have them stifled by school administrators who were shocked by the student’s language and who denied that children could even have had the experiences with pimps and drug-pushers that they wrote about so vividly.

Throughout his career, Kohl has continued to write about the concrete difficulties of teaching caringly and effectively in American public schools. Only he and Herndon havedevoted their attention so fully to discussing most imaginatively and most practically what can be done for pupils, and how to get it done in a conventional school setting. Kohl’s bookGrowing minds: on becoming a teacher (1984) is a small masterpiece, at once a moving autobiographical account of his motives in choosing his profession and his formative experiences along the way, and a series of finely honed, detailed case studies of classroom problems and how to deal with them effectively. The book is seductive, yet honest:

I am sorry to make learning to teach well seem like such a lonely activity, but it has been that way for me. Forover twenty years now, I’ve tried to talk with colleagues and administrators about educational ideas and thingsthat have a chance of interesting and challenging students, and have generally received stares of in comprehension. It wasn’t so much that the educators didn’t like me or my ideas, but that they had settled intothe established curriculum and it had settled into them. Teaching meant performing a series of tasks within a settime without losing control. The teacher as skilled craftsperson or creative artist was not part of the image theyhad of themselves (Kohl, 1984, p. 137).

Jonathan Kozol’s career has taken him a long way from his beginnings as the undergraduate, though even then radical, editor of the Harvard crimson. His first book, Death at an earlyage (1967), dealt with the wretched treatment of black children in the Boston schools of theday. It is an angry, poignant and wholly authentic indictment of indecent school practice; butKozol’s underlying interest lies primarily in the processes, and the effects, of impoverishment and exploitation in which schooling plays so important and so ambivalent a part. He has continued to write about schooling: Children of the revolution: a yankee teacher in the Cubanschools (1978) is a warmly sympathetic though occasionally critical account of Cuban schools Kozol visited in 1976 and 1977 (he didn’t teach there); and his most recent book, Savage inequalities: children in America’s schools (1991), shows how tragically little haschanged fundamentally since he wrote Death at an early age. Rachel and her children: homeless families in America (1989), perhaps his finest work, is about the far more serious underlying problems of poverty in the United States. Kozol, too, cites Goodman approvinglyin his writing, but his understanding of poverty makes Goodman’s seem almost frivolous.

Among this group of ‘romantic critics’, Goodman now appears to have been, in asense, central. He was the earliest, and the first to die. His influence has been the most frequently acknowledged. His way of looking at the plight of youth in society was prophetic and trend-setting; and his influence on discussions of education, if not on the practice ofschooling, has been profound. His attitudes toward sexuality and sexual expression inschooling were as exemplary as he could make them and, had they proved acceptable, wouldhave altered the conception of sexual abuse and deprived our culture of the materials fromwhich it weaves its most destructive scandals. Until Ivan Illich’s De schooling society (1971)appeared in the year before Goodman’s death, he was both chief iconoclast and icon among left-leaning critics of education; and even today, it is he who is most likely to be rememberedas our representative. Yet he had less to do with actual schooling than any of us: even I, who never attended school until I went to college.

Is this a paradox? I think not. For the striking fact is that none of us could bear theschools we criticized for long. None of us stayed there; we each escaped by one of twodifferent routes. Dennison and Kohl spent most of their later years in the deep woods of, respectively, Maine and northern California, continuing to interest themselves in local schoolissues and, in Kohl’s case, directing a summer camp for youngsters with learning difficulties.The rest of us, as I have indicated, either lost interest, like Holt, in the schools as such; orwere shocked into a broader and deeper interest in just how a society that could support such institutions and compel its young people to attend them functioned. Cui bono? Quis custodietipsos custodes?

In thus broadening the inquiry, Ivan Illich was to surpass us all. A Jesuit priest, bornin Vienna in 1926, he burst meteorically into the arena of educational conflict through hisinspired work with illiterate young Puerto Ricans in New York City. As founder of the Centerfor Intercultural Documentation (CIDOC) in 1964 in Cuernavaca, Mexico, Illich played hostto most of us, including Goodman in his final years, for seminars which confronted issues far transcending education. This is not the place to attempt a summary of Illich’s contribution; herequires and deserves a Profile of his own. Suffice it to say that schooling served him as ametaphor for the processes of alienation and excessive technological development in all areas of social and economic life that he proceeded to explore in such works as Tools forconviviality (1973) and Medical nemesis (1975), among many others.

Meanwhile, to be sure, other schools of criticism distinct from the ‘romantics’continued to develop in America. Radical critics like Michael B. Katz (1971), Joel Spring(1972), Clarence Karier (1975) and Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis (1976), while sympathetic to the issues we ‘romantics’ had raised, rooted them much more firmly in afundamental economic critique anarchist or neomarxist as the case might be. Antithetically, conservative critics of schooling sought means of making the schools more effective instruments of socialization, and of raising standards of academic achievement or at leastarresting the decline they believed to be taking place. Some, like Diane Ravitch (1978) engaged the radicals directly. Others, like David P. Gardner (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983) and Theodore Sizer (1984), among many mainstream critics, accepted the conventional mission of the schools with little debate as they devised means ofmaking them more effective instruments for, primarily, increasing the competitive advantage of American society.

This viewpoint now dominates, as it has for some years, the continuing debate about the purpose and quality of American schooling. ‘Excellence’ and ‘literacy’ become recognized as code words referring to the mastery of a traditional curriculum and of the skillsand, especially, the attitudes required for successful job competition, if only because prospective employers demand the credentials that attest to them. American schooling has always been primarily job-oriented; indeed, compulsory schooling up to mid-adolescence is acreature of industrialization that became widely established throughout the world as nations developed and took on their modern form: developing nations, as Illich stresses inDeschooling society, almost routinely seek to establish compulsory school systems that, if fully implemented, would bankrupt them at the outset. But traditionally, other important claims have also been advanced on behalf of State-supported schooling: the need for an informed electorate, and for the recognition of a shared, common culture. These arguments are certainly still advanced often with mounting anxiety as the schools are seen to fall farshort of achieving them. But they become less compelling as the conflict of interest between classes and among organized interest groups obscures the vision of a common culture; andthe schools become more explicitly recognized as essentially a part of the mass media, atleast as subject to censorship and control as film or television. Joel Spring’s Images ofAmerican life (1992) provides a convincing historical analysis of this development.

At this juncture, Goodman’s relevance confronts a paradox. It is now clear that,despite the limitations imposed by his narcissism, his vision of schooling and its deficiencies was precise. American culture, including schools, has developed much as he warned it might.But this surely means, as he might have predicted, that his counsel will continue to gounheeded, dismissed as quaintly tainted with the inexpedient idealism of the 1960s; and as blindly reluctant, despite his patriotism, to celebrate America’s position as permanent acknowledged leader of the forces of freedom in the world. A surprisingly large number of 16 people share this reluctance. The problem is that, as American educators continue to narrowtheir claims on education, merely demanding with mounting urgency that it serve the ends of national leadership, the problems of schooling become, if no less important, certainly less distinctive and therefore less engrossing. As Goodman would surely have acknowledged,there is nothing wrong with American education except what is wrong with American society.

Note

1. Edgar Z. Friedenburg (United States of America) Ph.D. from Chicago Universtiy. Author of The disposal of liberty and other industrial wastes (1975), and Deference to authority: the case of Canada (1980, among other works. He taught at several universities in the United States before emigrating toCanada in 1970 where he was appointed Professor of Education at Dalhousie University, Halifax;professor emeritus since 1986. His chief interest is in adolescent socialization, and he now devotesmuch time to the gay and lesbian communities.

References

I Goodman, P. 1954. The structure of literature. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press. [DoctoralDissertation]

–.1959. The empire city. Indianapolis, IN, Bobs-Merrill.

–.1960. Growing up absurd. New York, NY, Random House.

–.1962a. Utopian essays and practical proposals. New York, NY, Random House.

–.1962b. The community of scholars. New York, NY, Random House.

–.1963. The society I live in is mine. New York, NY, Horizon Press.

–.1964. Compulsory miseducation. New York, NY, Horizon Press, 1964. [Reprinted with The community ofscholars. New York, NY, Vintage, 1966. Page references are to this edition.]

–.1965. People or personnel: decentralizing and the mixed system. New York, NY, Random House.

–.1966. Five years: thoughts during a useless time. New York, NY, Brussel & Brussel. [Reprinted as aVintage paperback in 1969.]

–.1967. Like a conquered province: the moral ambiguity of America. New York, NY, Random House. [TheMassey Lectures]

— .Goodman, P. Communitas: means of livelihood and ways of life. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press, 1947.

Perls, F.; Hefferline, R.; Goodman, P. Gestalt therapy: excitement and growth in human personality. New York,Julian Press, 1951.

References II

Apple, M.W. 1979. Ideology and curriculum. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. 1976. Schooling in capitalist America: educational reform and the contradictions of American life. New York, NY, Basic Books.

Dennison, G. 1969. The lives of children. New York, NY, Random House.

Friedenberg, E. 1959. The vanishing adolescent. Boston, MA, Beacon Press.

–.1963. Coming of age in America. New York, Random House.

Herndon, J. 1968. The way it spozed to Be. New York, NY, Simon & Schuster.

Holt, J. 1967. How children fail. New York, NY, Pitman.

–. 1981. Teach your own: a hopeful path for education. New York, NY, Delta-S. Laurence.Illich, I. 1970. Celebration of awareness: a call for institutional education. Garden City, NY, Doubleday.

–. 1971. Deschooling society. New York, NY, Harper & Row.

–. 1973. Tools for conviviality. New York, NY, Harper & Row.

–. 1975. Medical nemesis: the expropriation of health. Toronto, London, McClelland & Stewart.

Karier, C. 1975. Shaping the American educational state: 1900 to the Present. New York, NY, Free Press.

Katz, M.B. 1971. Class, bureaucracy and schools: the illusion of educational change in America. New York,NY, Praeger.

Kohl, H. 1967. 36 Children. New York, NY, New American Library.

–. 1984. Growing minds: on becoming a teacher. New York, NY, Harper & Row. [Published in paperbackas: On becoming a teacher. London, Methuen, 1986. Page reference is to Methuen edition.]

Kozol, J. 1967. Death at an early age. Boston, MA, Houghton Mifflin.17

–. 1978. Children of the revolution: a yankee teacher in the Cuban schools. New York, NY, Delacorte Press.

–. 1989. Rachel and her children: homeless families in America. New York, NY, Crown Publishers.

–. 1991. Savage inequalities: children in American schools. New York, NY, Crown Publishers.

Kuhn, T. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

Meikle, J. 1992. New Review of English Teaching. Manchester guardian weekly (Manchester, UK), vol. 147,no. 12, 10 September, p. 4.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. 1983. A nation at risk: the imperative of educational reform.Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ravitch, D. 1978. The revisionists revised: a critique of the radical attack on the Schools. New York, NY, BasicBooks.

Schrag, P. 1967. Education’s Romantic Critics. Saturday review (Des Moines, IA), no. 50, 18 February, p. 80-82.

Sizer, T. 1984. Horace’s compromise: the dilemma of the American high school. Boston, MA, Houghton Mifflin.–. 1992. Horace’s school: redesigning the American high school. Boston, MA, Houghton Mifflin.

Spring, J. 1972. Education and the rise of the corporate state. Boston, MA, Beacon Press.

–. 1992. Images of American life: a history of ideological management in schools, Movies, radio, and television. Albany, NY, State University of New York Press.

Stoehr, T. (ed.) 1977. Nature heals: the psychological essays of Paul Goodman. New York, NY, Free Life Editions.

–. 1978 1980. Paul Goodman: collected stories. Santa Barbara, CA, Black Sparrow Press, vols. I and II,1978; vol. 3, 1979; vol. 4, 1980.

Widmer, K. 1980. Paul Goodman. Boston, MA, Twayne Publishers.

Copyright notice

This text was originally published in Prospects : the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO : International Bureau of Education), vol . XXIII, no . 3/4, June 1994,p. 575-95.

Reproduced with permission. For a PDF version of the article, use:

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/goodmane.PDF

Photo source: paulgoodmanfilm.com. Copyright © 2008-2010 JSL Films.